Sam Ombiri shares thoughts on C.F.’s collection “Mere”.

—————————————————————————————————

Sam Ombiri here: The satisfaction in reading Mere by C.F. (PictureBox, 2012) is that C.F. isn’t deconstructing comics in a smart or clever way – one that’s lacking catharsis – but in an incredibly personal way.

These comics are amazing as a document, but I don’t want to reduce the work to just “document”. Art to me, as it’s considered a superfluous endeavor, is made 1000 times more useless, 1000 times less potent, when it’s forcefully made to pander to ideas of usefulness outside of art. To impose that brand of efficiency on art contradicts the final product as a work of art.

I was thinking of how in the comic Pompeii by Frank Santoro, Flavius’ paintings in that story are just used to block other things – one painting blocks all the ash and lava and fumes from the volcanic explosion taking place, while his other painting – the landscape – it’s only purpose is to cover up the affair he’s having with the princess. I was thinking about how Flavius’ paintings were reduced to props, to serve the one function of blocking a window (though I’m sure against Flavius’s will) and his other earlier painting, the landscape, just exists to cover up Flavius’ lies.

This is what I perceive to happen when art is forced to be made useful, when it’s made to lose all quality of being art, for the sake of being made useful. I mean, of what artistic value is Flavius’ painting? If the painting’s only function is to block all the ash, all the lava, all the sulfur, of what artistic value is Flavius’ painting? It was only Marcus’s drawing on the wall that was truly evocative and comforting in that moment when Marcus and Lucia were trapped in Flavius’ burning studio.

So back to C.F. – when I say Mere is a document, I mean a personal document of art in that it doesn’t care what it’s documenting. Rather it is more preoccupied with how it’s documenting it. I mean to say C.F. knows what he’s doucumenting, but we readers don’t know. Instead we feel. We feel what he’s documenting, based on comics we read in the book, and what C.F. has said about the comics that he made in this period. I can discern that the work is a personal document. Mere is a great document of many things that couldn’t otherwise be written by words.

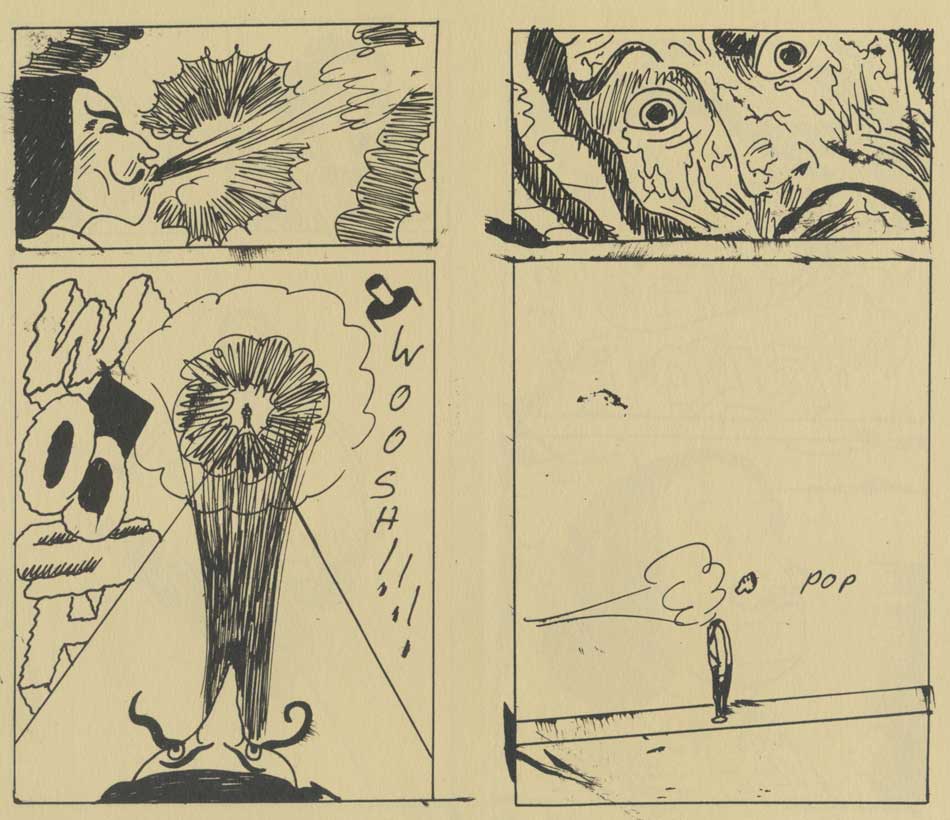

This might be a cop out on my part, except that I have a strong conviction that this is the case. While the work is all over the place – it is a collection of minicomics after all – there’s still a distinct focus throughout it in functioning as a personal document. C.F. had to invoke the environment in which it’s some manga he’d be reading – the whole thing with Main Dice for example isn’t isolated. The story is really straightforward, with undeniable moments that are undeniable perhaps because they are at the service of construct.

There’s a saying, “In rhythm there is image, in image there is knowing, in knowing there’s a construct” – so that’s to say there’s a real construct in the comic which gives us so little, yet because the comics are at the service of a construct, so deeply. I might add, when approached not as an obligation, but with natural sense of pleasure, it’s a privilege to be at the service of this construct. It’s the phrase “work of art” that I take to mean work coming out of art.

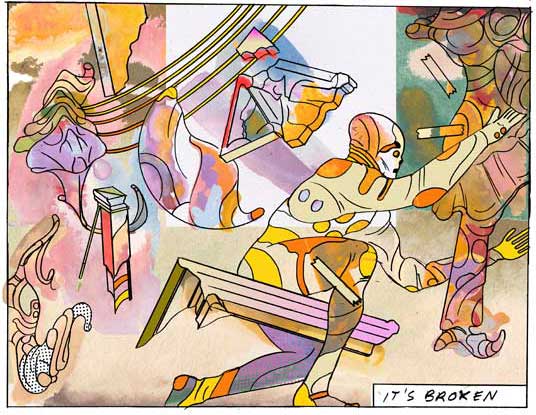

In the story Crossdown the wrong part of the broken projector falls down and continues it’s decent, past the character who was deeply affected by a movie at the beginning of the story. The story doesn’t focus on this character, so we don’t even know this character’s name. This scared character is coming out of the movie theater, still experiencing terror from the movie which was being projected at the same theater where that broken part was tossed out the window. This broken part is then kicked down by the scared man into the basement or underground passage in which Main Dice is navigating. Main Dice is hit on the head by this part – the scene is drawn with the anticipation of the broken part falling on his head. This prompts Main Dice to shine the light to see what hit him as it had landed on the floor of this now dark room. This leads him to discover a motorcycle. Now, the plausibility of these moments especially register. This story is at the service of a construct – it has rhythm (which it later purposefully forsakes in order to rush itself in a different direction, to make some sort of a discovery – my guess is that it was the scenario taking priority, maybe becoming self aware or rather portrayed as becoming self aware, and then portrayed as becoming completely selfish in that it engulfs the entire comic, forsaking all other elements that made it up).

When reading C.F.’s contribution to Kramers Ergot 8, (which I believe was done around the same time as some of the comics in Mere) I have to wonder where did this comic surface from? The placement in Kramers #8 makes it out to be something that somehow just makes sense for it to exist – but it doesn’t make any sense for the comic itself to exist, despite its existence. I heard C.F. say that if you find a zine just anywhere, you just don’t know. With these comics in Mere I just don’t know. C.F. was saying he wanted to make a that has a manga attitude, and he suggested that for manga the editors are more preoccupied with the characters, rather than the scenarios. This immediately made me think of Sammy Harkham, who was C.F.’s editor (for Kramers #8) talking about how before anything else he wants to know where a story takes place, and what that place might say about a character. What I take away from that, is that the reality of the comic might as well be a character in an empty space (like one of those comics Anders Nielsen did when switching up his style in Monologues For The Coming Plague.) Personally that’s what drew me to reading comics, but not in such a conscientious visceral manner – it was rather just something at the back of my mind.

I know C.F. is always claiming that his work is made for him to be comfortable and that he likes how his work challenges him. He enjoys that the challenge presented in front of him is scary. That it’s scary is what makes it interesting, and he wouldn’t enjoy it otherwise. So his work is at the service of the art form as a result. When talking of the nature of the work in Mere there was a vaguely apologetic tone and small sense of regret that the work is selfish and not serving the form as it ideally should for him (or so it would seem). This form that utilizes, or rather is utilized by, simple shapes like circles, squares, triangles which according to C.F. seem too universal to penetrate, because they’re too simple and refer to too many things. In the same way a basic shape like a circle or square or a triangle is broad, C.F. is presenting the idea of comics in the broadest sense.

In the same way simple shapes are difficult to penetrate these comics are also difficult, because in a personal way C.F. has condensed genre, and what not. As the reader, I can only guess at how it conceptually ties to how comics function. However, C.F. himself said if he was condensing genre it’s in a personal way. Similar to his name when making comics (C.F.) it is aesthetically driven, not imbued with the idea of efficiency. If it were otherwise, the other aliases he’s had would be shorter for the sake of simplicity. Case in point – his other aliases like Brown Recluse Alpha or Universal Cell Unlock. If efficiency was in mind with the name C.F. as opposed to Christopher Forgues, it’s to reflect the inefficient efficiency of cartooning. The most efficient thing when wanting to show an image is taking a photo, or rendering something as realistically as possible so that there’s no opportunity for failure in communicating; not cartooning.

It’s like the title Mere. Mere what? How many more marks can evoke with so little? Not that the significance lies purely on this aspect of a little doing a lot. Again, it’s not doing a lot. Again, not for the sake of efficiency; to optimize what can be accomplished and what can be done with so little. If comics were at the service of efficiency and optimization, in the sense that it’s already been made known ahead of time everything that a comic is exclusively able to do, what possible need is there for to work to be read? If work is purely to pander 100% to one’s sensibility of cool, because it exists only for the sake of efficiency and nothing else whatsoever, what can it possibly offer as art?

To an extent in the comics in Mere these questions are asked. It takes so much to convey things sometimes, and sometimes so little. One often needs to pander to the more in-optimized zone of cartoon or as C.F. put it, in a more romanticized fashion, “Turning your back on everyone you know, turning your back on your whole life so that things can come out that you didn’t plan or you don’t intend, things you don’t understand because that’s what art is for, that’s what creativity is for, to ask questions. Questions you have aren’t always the questions you think you have.”

Mere possesses comics that subvert genre by condensing them in personal ways, possibly in ways that change our outlook entirely or have shifted our outlook in a direction that hasn’t been determined – rather it’s all questioned, i.e. “turning your back.” There are certain stories in Mere that are purely straightforward. That the focus is more on the scenario takes priority, and so the story carries on in this way. Like this character Main Dice, who we know next to nothing about. In fact, in his second appearance, he is completely redesigned. From my vantage point, this is not done in order to comment on how in manga a timeskip happened and all the characters are completely redesigned, for example like when Dragon Ball became Dragon Ball Z, and the characters have grown up. Then there’s the element in American comics there are multiple versions of superheros – like how there’s the Blue Beetle called Ted Kord, and the Blue Beetle called Jaime Reyes; or how there’s the Robin called Dick Grayson or the Robin called Jason Todd and there’s the Robin called Tim Drake.

Main Dice’s redesigns, to my understanding, aren’t a comment on all this. It seems to me that what it is instead is a document of the personal effect these aspects of comics have had on C.F. Even as I had recently, on a whim, read the third volume of Dragon Ball Z (which is really amazing,) I couldn’t help but identify with what C.F. had said – that the tendency in manga is that the editors are more preoccupied by the scenario than the characters. I’d zipped through 174 pages of action without realizing it, and the nature in which the action was being communicated was the same nature in which most of the comics in Mere unfolded – especially the first two comics in Mere that feature Main Dice. – Sam Ombiri

Get a copy of Mere by C.F. HERE!

—————————————————————————————————

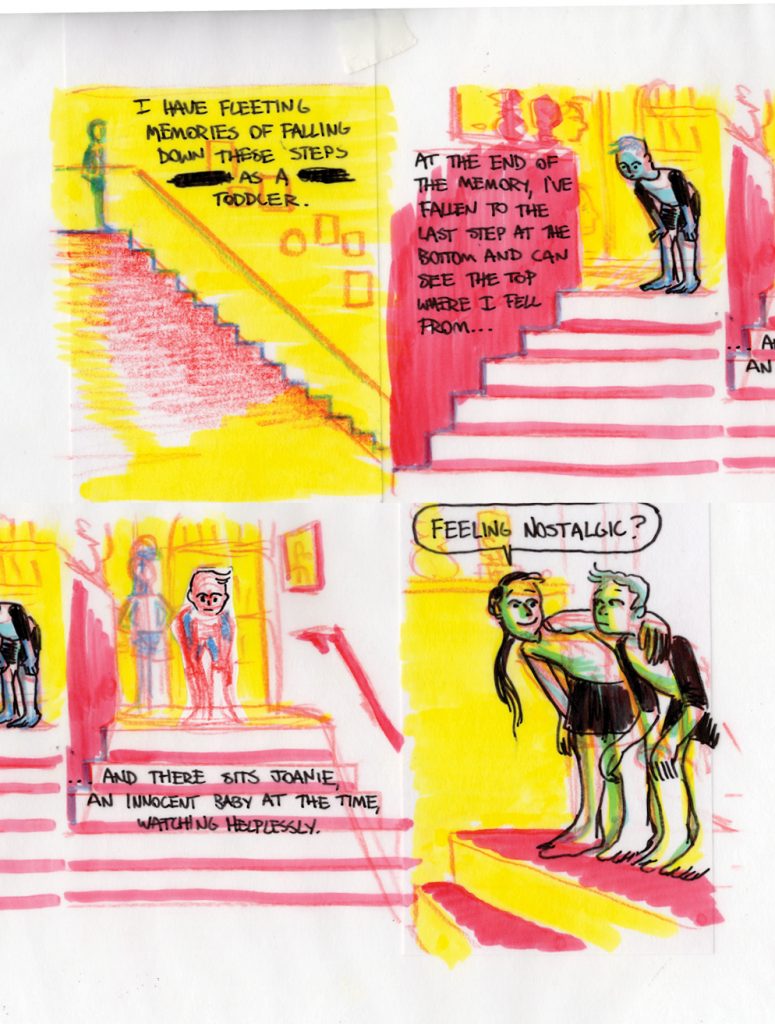

Joanie and Jordie – 6-28-18 – by Caleb Orecchio