Sam Ombiri on Patrick Kyle’s Everywhere Disappeared, plus other comics and news!

—————————————————————————————————

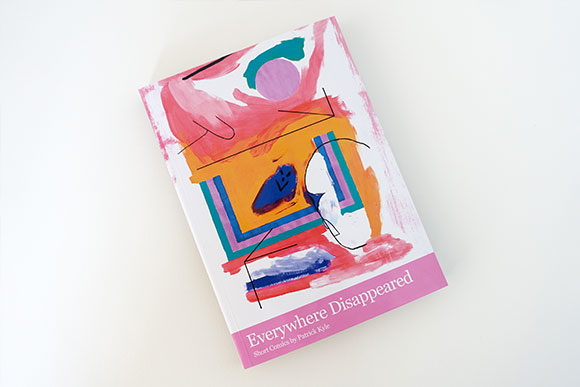

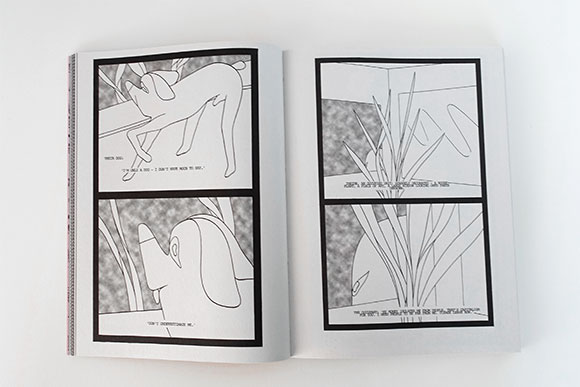

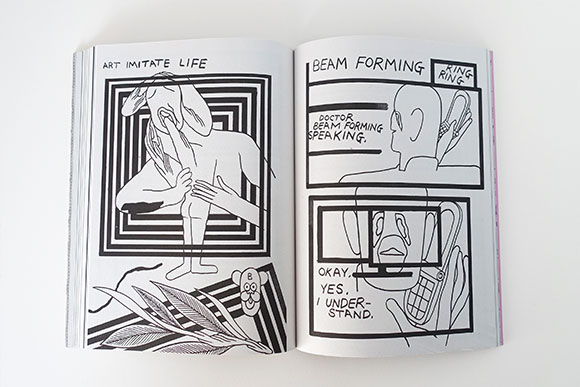

Sam Ombiri here: I had a chance to read an advanced PDF copy of Patrick Kyle’s new comic Everywhere Disappeared. (The book has now come out from Koyama Press.) At first I had trouble with this book, but I took the time to read through it twice and I made many discoveries. There is part of the book that feels rather navel-gazy and a bit vain as a result, (for him to be showing work like this). This was an initial misinterpretation on my part, because it looks at first like this new book is just a reflection of how Patrick is a private person. From what I’ve heard him say about this, he is pretty private, and he’ll keep many elements of his work that could be interpreted as personal, hidden. The work then feels somewhat rigid when he’s documenting what we might see as his artistic struggles, and personal struggles. Being who he is, he is doing this in a really roundabout way, and while I enjoyed the book, it’s a little bothersome to sit through. (Although the bothersome aspect became the interesting aspect later.)

When I first read the second strip I thought to myself “Does Patrick think his work is in so much demand that we’re willing to sit through this nonsense?!” It’s not as focused as his last book (Don’t Come In Here, 2016), which might answer why any emotional triumph in the beginning of the book feels unearned, and this made me a little nervous, because that was a problem I had with certain parts of Don’t Come In Here. Now I had to read a whole book that was filled to the brim with that problem? I discovered that I should not have worried.

I felt at first that there wasn’t any long term investment to be had with Everywhere Disappeared, but as I read more and more of the book, I was proven wrong. Patrick has a big artistic triumph.

Everywhere Disappeared is a collection of stories in the form of comic strips. Taken together the book seemed to me to be about taking risks, and people reacting to your insincerity, be it through art or just normal interaction. The first strip functions really well in telling the reader what mindset Patrick is in. The strip that follows just baffled me in how much he’s testing the reader’s patience, as I mentioned above. Then I had to eat my words with the following strips, which were just amazing – hilariously portraying his solutions to his dilemmas in his current role (with the sentiments expressed in the first and second strip, and the answer being the third strip.) Point being, though I felt at first that the second strip was a lousy strip, it really served the book well. It was a step up from just being a self-conscious comic, a major step up – instead of stagnating with his self-consciousness, he advanced. Not only that, but it tells you as the reader that Patrick isn’t suddenly making these big conceptual leaps as a maker. He’s still this guy who you come to to read some fun stuff, and he’s still very much thriving in this territory.

At a certain point as a reader of Everywhere Disappeared, even looking back at the Dracula story (the second strip), I realize it’s been really fun and it’s going to continue to be fun. The illustrations are getting tastier and the punchlines are getting funnier. The ridiculous concepts are more acceptable to the reader. There a style that was introduced in the Dracula strip, then a couple strips later we get the pay off with it. Amazing pay off too, when a character does a print with Bart Simpson with Nike for eyes (and that gag only manages to get better). It reminds me of a gag I’d see from Ben Jones, but it’s all Patrick Kyle.

By the time I read the strip titled “Glory of the Pile” I knew that I was completely wrong in thinking that Patrick was running out of his bag of tricks. That strip hit me hard. There’s a real impressive element to how Patrick is recycling shapes he normally draws and just uses them here and there, to elicit some kind of emotion or feeling or sentiment he’s trying to get across to the reader. The book speaks its own language now and is super comfortable in it, and this seemingly comes out of nowhere (or everywhere?). – Sam Ombiri

Get a copy of Everywhere Disappeared HERE.

—————————————————————————————————

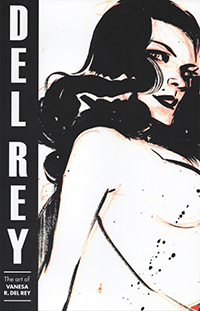

Sally here – The Art of Vanesa R. Del Rey was reviewed as an Orbital Comics staff pick recently (Orbital Comics is currently hosting a show of Vanesa’s work!).

“Thomas says: I wasn’t aware of Del Rey’s art until her work came in for the show that is currently running in our gallery (until the end of the month) and was absolutely blown away by what I saw. Her work is gorgeous, her line work free and energetic with an exuberant life of it’s own. Even static figures seem to be in motion, breathing with a life of their own.

This sketchbook serves two functions; it is a beautiful selection of Del Rey’s work but is as much a glimpse into her life, past, present and future as it is anything else. Interviewed by Frank Santoro, Del Rey is open and forth coming about her work explaining as best as she can her thoughts regarding the human figure, to the influence art has had on her life and is also quite open about her life and her childhood.

With a new book out this past month written by the wonderful Jordie Bellaire, Del Rey’s star is in the ascendant and you would be foolish to ignore this talented young artist. Excitingly, Vanesa will be signing here on Saturday 16th September 2017, from 17:00 till 19:00 so come along and pick up a copy of her sketch book or Redlands and say ‘Hi’. Click here for more details.“

Get a copy of The Art of Vanesa R. Del Rey HERE.

—————————————————————————————————

There’s a piece in the Washington Post‘s Comic Riffs about Shawn Martinbrough, and how he came to draw Hellboy in a recent one-shot issue of Hellboy and the B. P. R. D. Heavily influenced by the artwork of Mike Mignola as a kid, this was a dream project for Martinbrough, who has been storming the mainstream comics scene for a few decades (more on his story HERE).

“Martinbrough…is known for going out of his way to add diversity to the comics he works on. If a story’s script doesn’t specify the race of a supporting or background character, he’ll frequently draw that character as a person of color.

That wouldn’t be necessary with this Hellboy story (written by Mignola and Chris Roberson), in which Woodrow, Hellboy’s partner, is a brilliant African American from Chicago.

In the story, Woodrow is offended but not shocked when he brushes up against some racism even noticing that the white man he and Hellboy have questions for is more comfortable around a giant demon from hell than a black man.

“Hellboy is an average Joe in the form of a large, fantastical red demon with a large stone hand and tail,” Martinbrough said. “The idea of a white guy accepting Hellboy without skipping a beat, but questioning the legitimacy of a black scientist is tragic but, unfortunately, very realistic. The social commentary was a very pleasant and welcome surprise.”“

—————————————————————————————————

Suzy and Cecil – 9-14-2017 – by Sally Ingraham