I’ve been meaning to write something about these comics since I found out about them a year ago. Before this I never knew my parents read comics in their youth. They both grew up in Mexico (b. 1964 and 1966) in small pueblos, and left their houses at 14 and 19 to work.

I was so curious as to what interested them enough as kids to capture their attention week after week. What captivated them had to actually interest the town as a whole in order to be read. They explained that children in the pueblos were poor and could only afford an issue here and there, and swapping comics with other kids was the only way they could finish the adventures. Even more removed – they paid to read to whichever child in the pueblo had the issue they needed to read next.

For reference of the sort of social ecosystem my parents grew up in, my father herded sheep on a mountain and my mother was from a poor family of 5, leaving her house at 14 to work at an orphanage. Their childhood has eluded me most of my life, and I was curious as to the kind of stories that would be popular to humble roots like theirs.

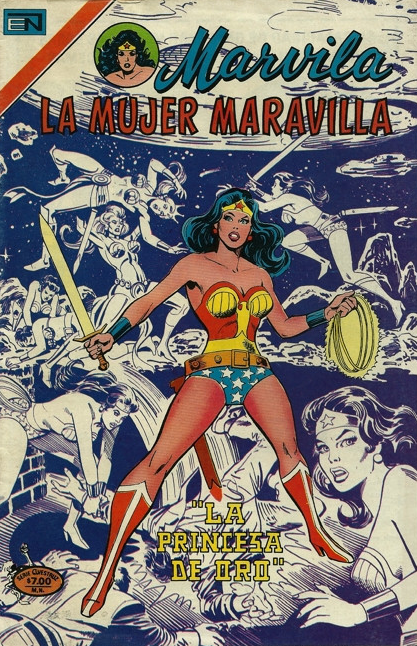

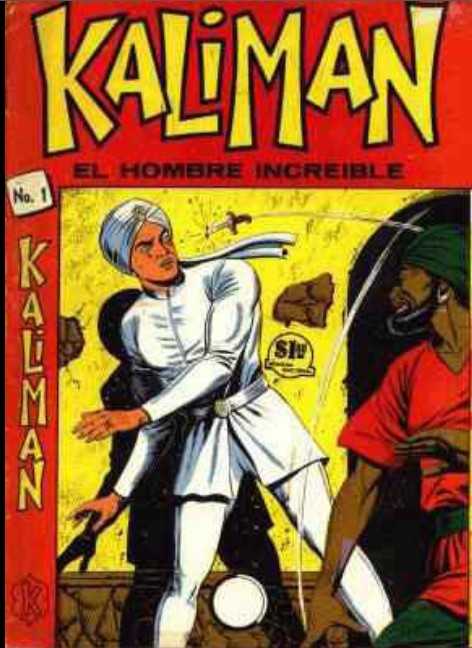

The majority of the comics I will be introducing were created in the 1960’s and 1970’s. From the 1930’s to the 1970’s the comics industry was strong in Mexico, with their own original titles in addition to translated American versions. La pequeña Lulú (Little Lulu) and La Mujer Maravilla (Wonder Woman) – both pictured above – were enjoyed, alongside comics of Mexican origin such as Chanoc (1959), Kaliman el Hombre Increible (1965), Rarotonga (1951), and Hermelinda Linda (1965) among many others.

—————————————————————————————————

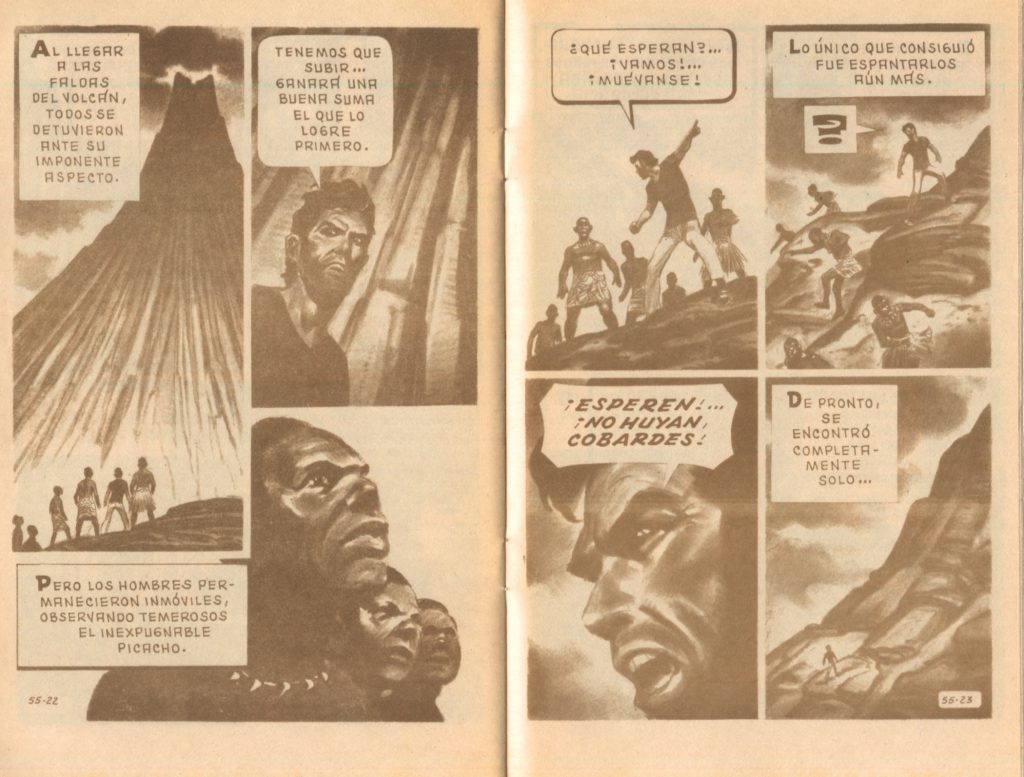

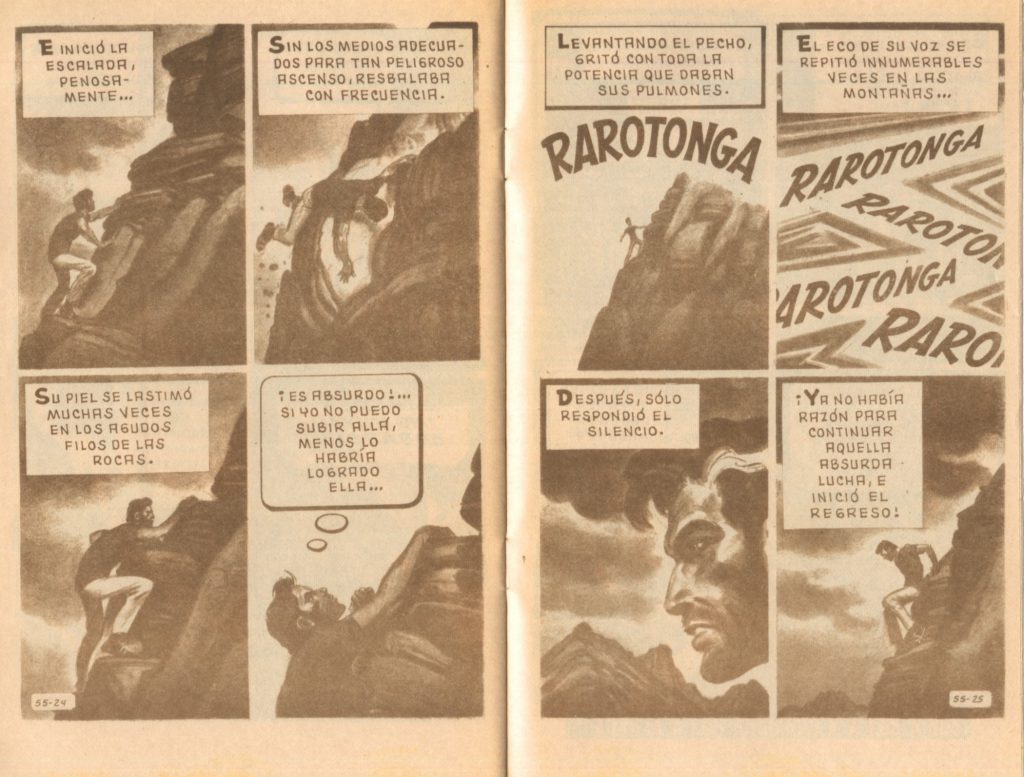

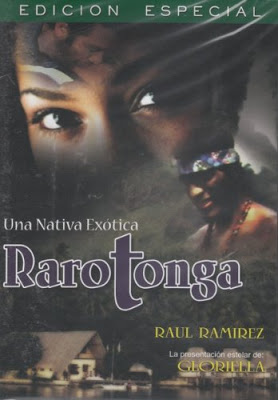

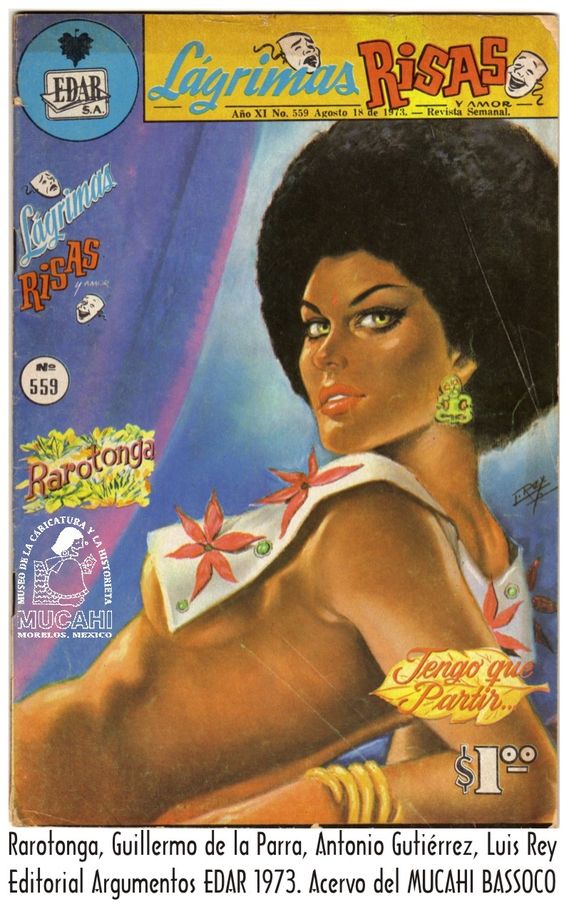

Going by year of debut, Rarotonga is a series within the larger comics title of Lagrimas, Risas y Amor (Tears, Laughter, and Love) published by Editorial Argumentos (also known as EDAR). Rarotonga is drawn by Antonio Gutierrez and has a total volumes of 216 issues. Other titles by Gutierrez include Yesenia, Rubí, and El pecado de Oyuki.

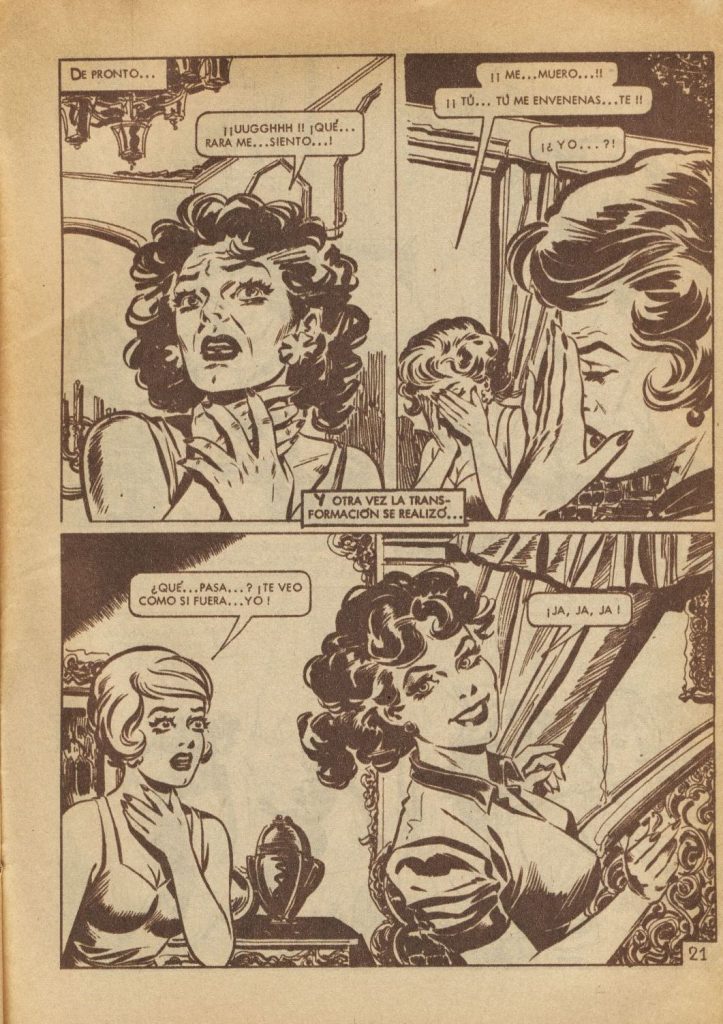

Rarotonga (excerpted from above) tells the story of a jungle queen/goddess of the eponymous island, who seduces a professor/doctor visiting the isle – she is the goddess of love and death after all (as are all women). She has special powers she attempts to use upon the foreigner (who needs lust when you can magically seduce any man with your powers, right?) However he seems to resist her – for the sake of his pre-established marriage. Rarotonga is essentially a jungle-novella, suitable for the publication Lagrimas, Risas y Amor which ran romance comics, which were often adapted into films and telenovelas.

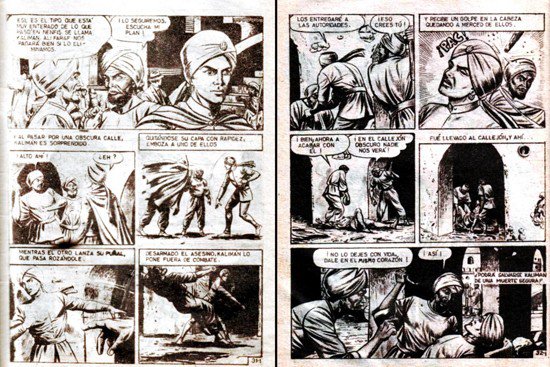

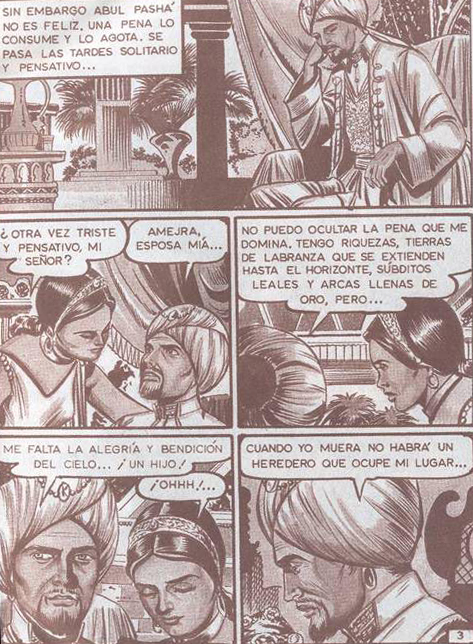

The story itself is more than a trashy love story, as it also touches on themes of western civility and reason against uncolonized magic and lust. Visually, Mexican comics around this time have this value-heavy shaded look to them, and as the distribution later increased for comics in Mexico the comics were reprinted in color (speculatively lowering the quality of the comic artwork). The sepia tone comics (Rarotonga and Kaliman) initially enjoyed at fully newsprint size, later were reduced to the size of a pulp novel (4.5 x 7 roughly). Eventually comics in Lagrimas, Risas y Amor reached audiences in Spain, Venezuela and even Japan.

The bodacious Rarotonga was liked by women as much as men. In a society where machismo reigns, Rarotonga piqued the interest of young women. (However, as it was told to me, boys would tease girls in the pueblos with big asses – calling them “Rarotonga”!)

—————————————————————————————————

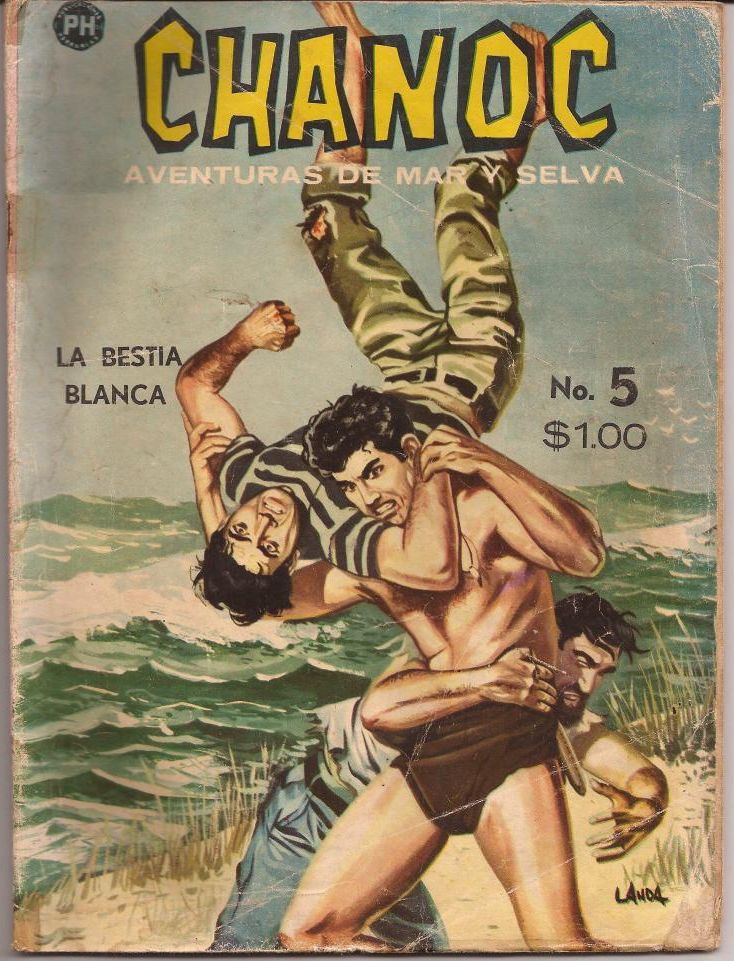

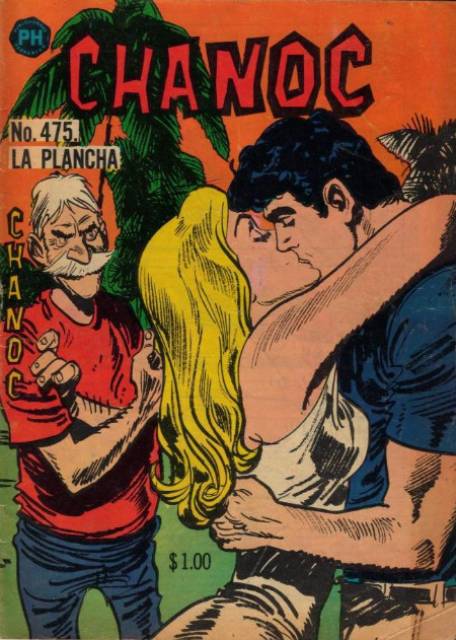

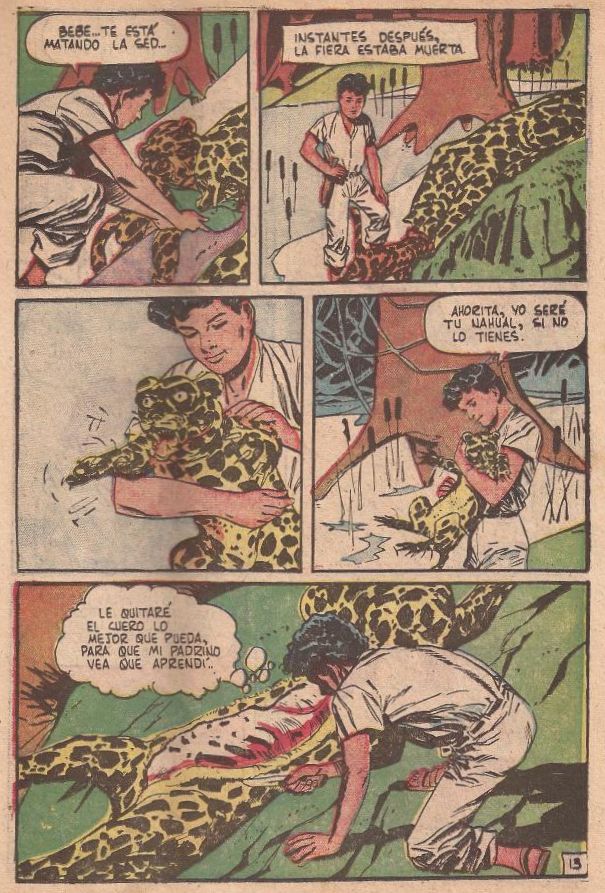

Chanoc, written by Martin de Lucenay and Angel Mora, are “adventures of sea and jungle”, that take place in the Gulf of Mexico. Chanoc is our rebellious hero who little by little sees a change in character as he adventures and protects his older godfather, Tsekub. Chanoc is developed within the port of Ixtas – the names and setting are all of Mayan origin, Chanoc being a deity in myth, but a pearl diver in this adventure. This is interesting because in Mexican comics history, pre-Columbian codices are arguably Latin America’s earliest form of comics.

Mora draws Chanoc influenced by 1950’s and 60’s American comics, without letting go of themes and story traditions found in Mexican comics. Chanoc begins as a simple story of a young man against the sea, but eventually our protagonist is responsible for convincing the Mexican government to spend their economic resources on feeding the hungry instead of contracting more arms. This is all done with a flair of humor of course, which reflects on Mexican cinema of the time (Cantinflas and Tin-Tan) – political but humorous.

—————————————————————————————————

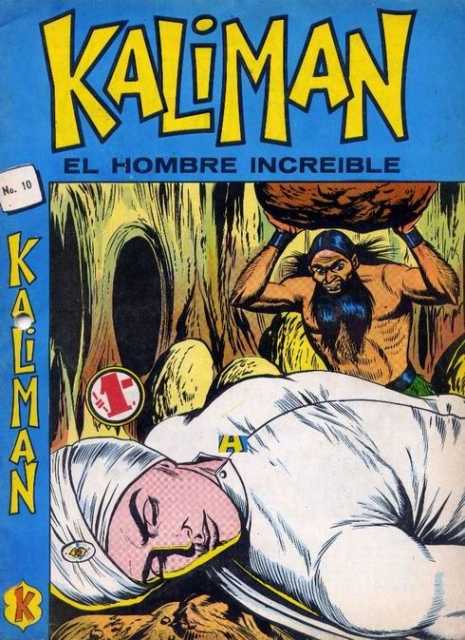

Kaliman (above) is one of the most popular Mexican comics, which ran for 26 years starting in 1965. The first printing of 100,000 copies sold so quickly it had to be reprinted the same week of its launch. The series covers 39 different stories from 1965 to 1991. The story of Kaliman began as a radio show, in 1963, and with popularity became a comic book in the next few years. The comic is drawn by Rene del Valle.

Kaliman is born in a fictitious setting in India. In the kingdom of Kalimantan he is found in a floating basket by a prince, Abul Pasha, who adopts him as his own son. Kaliman is later kidnapped with the intention of murder, and escapes. As Kaliman’s quest continues, he travels to other regions such as Tibet, and develops himself through teachings of judo, karate, and jiu jitsu, defeating enemies and defending justice. Like Rarotonga, Kaliman was originally printed in sepia tones, with an unpopular color reprint afterward.

—————————————————————————————————

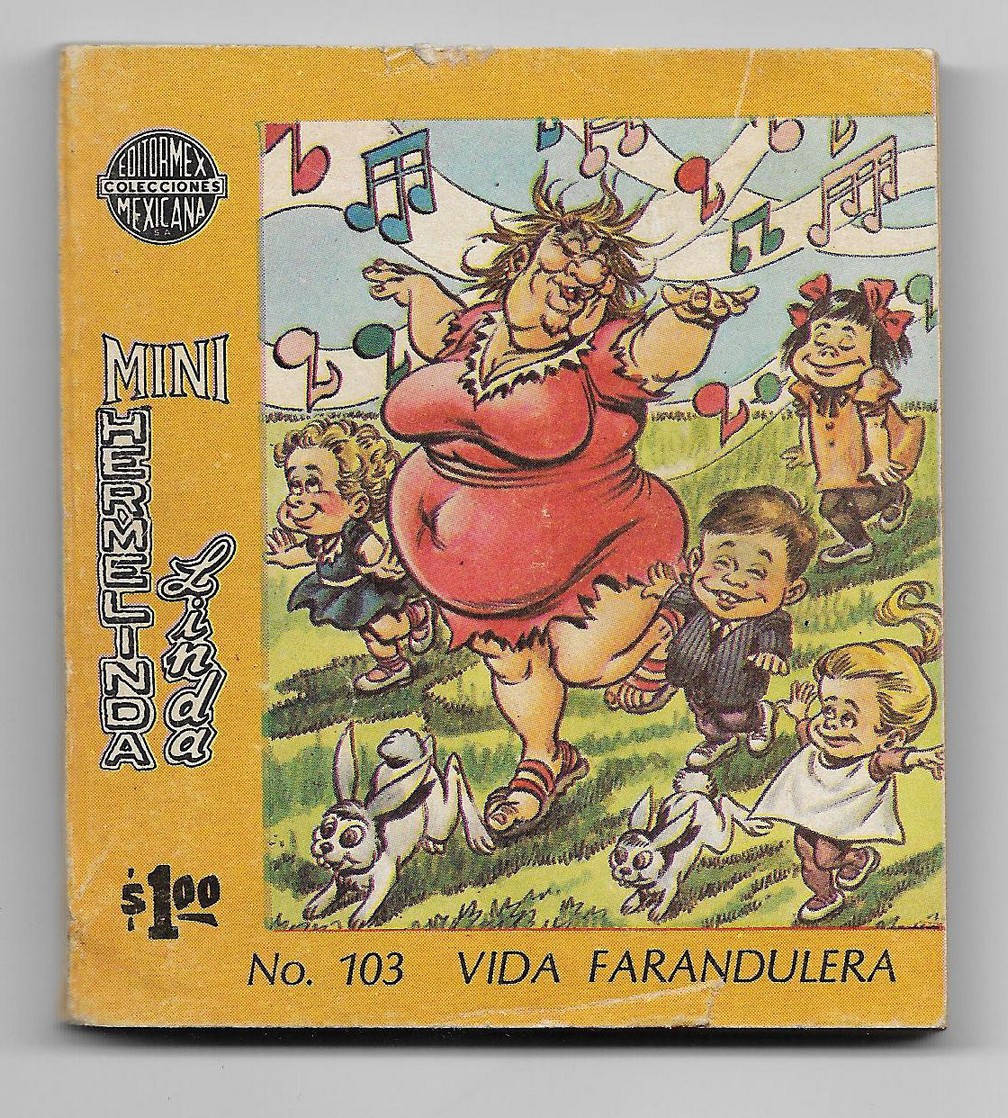

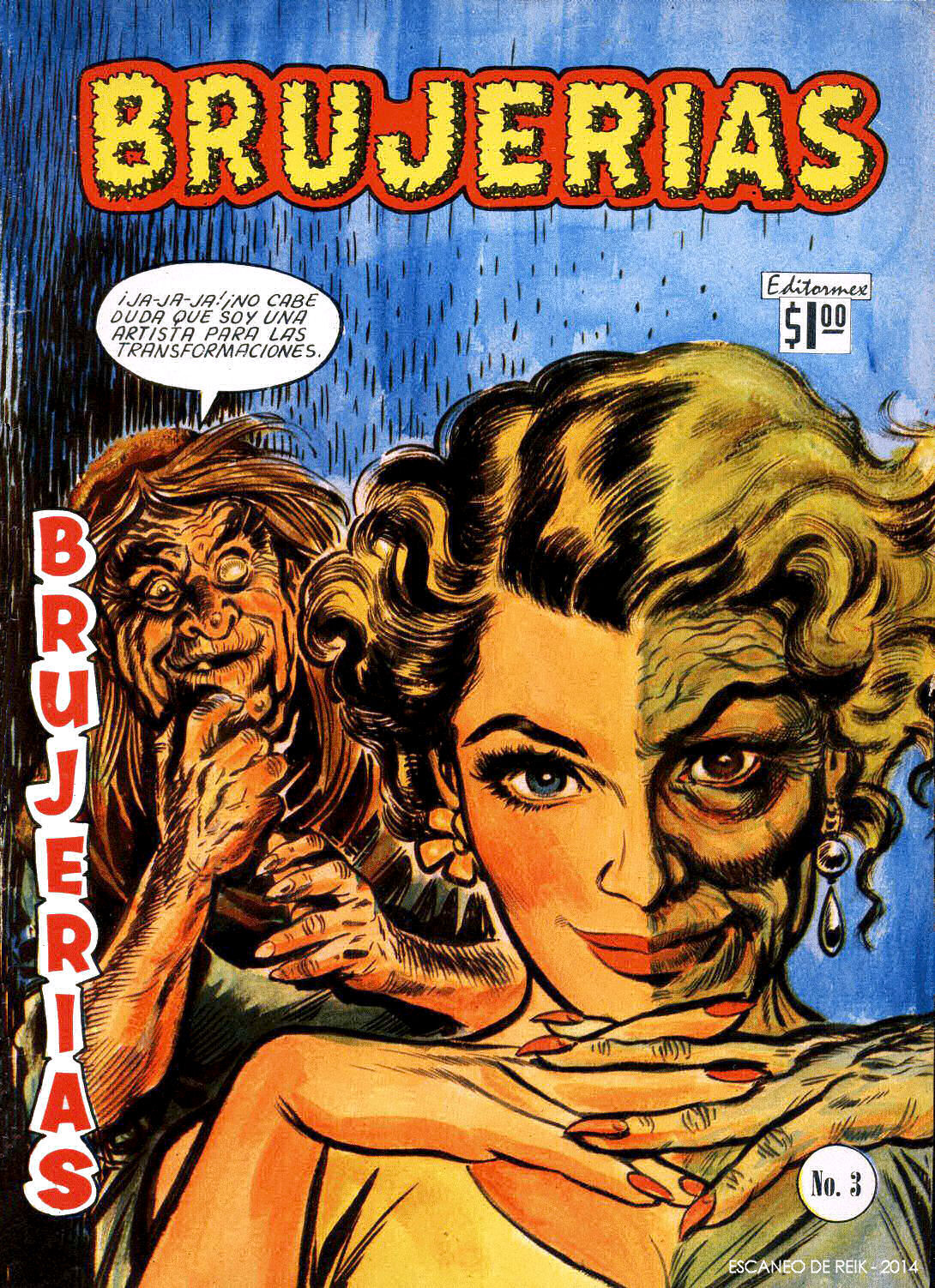

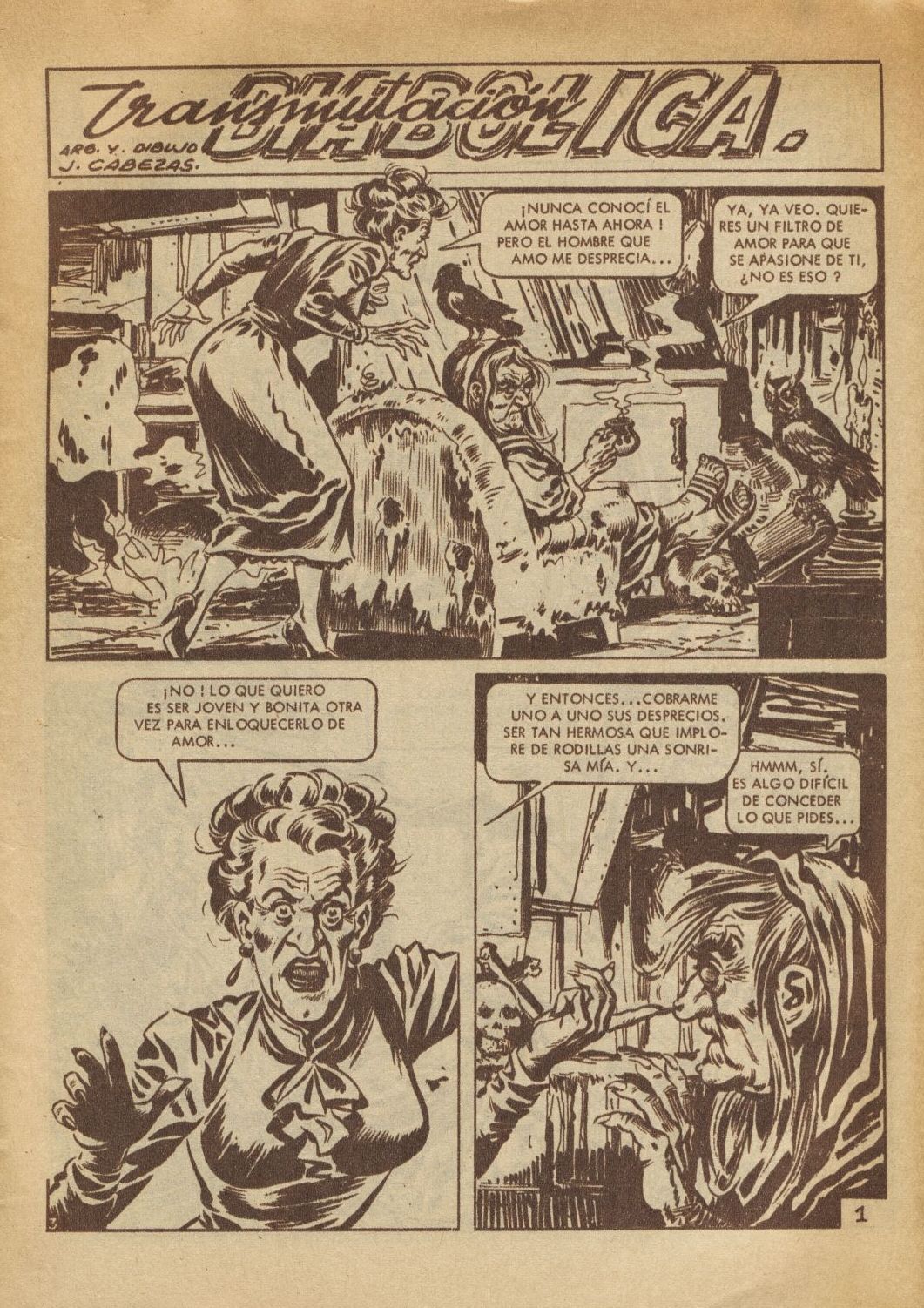

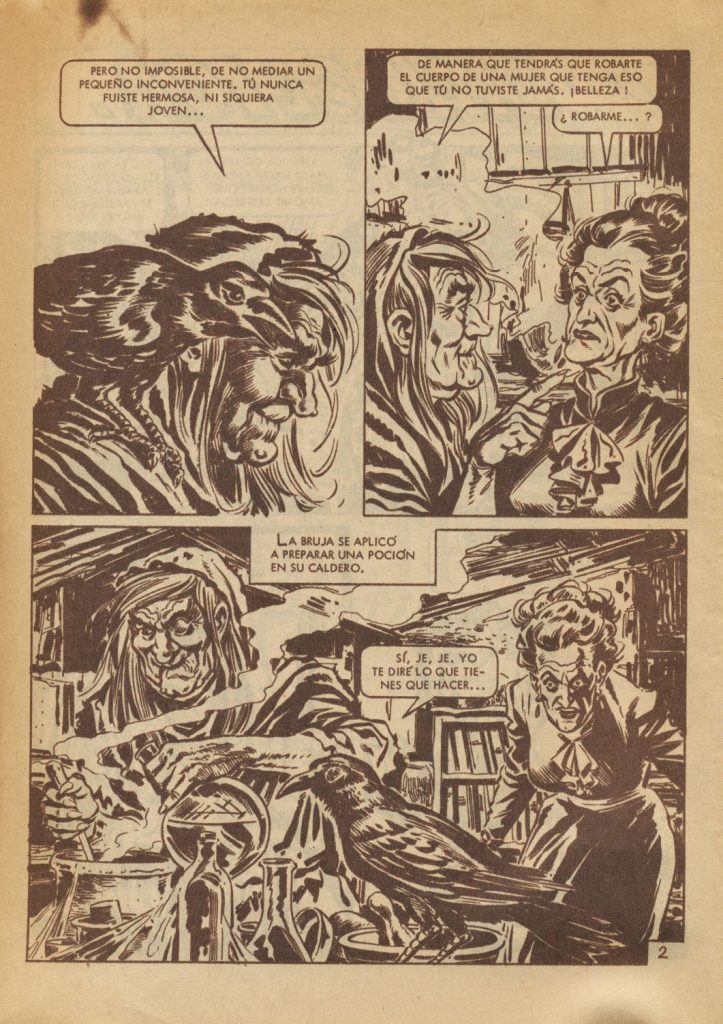

Hermelinda Linda is a satirical comic published between the decade of the seventies and the end of the eighties in Mexico by Editormex Mexicana, and later released as two films. The author of the original Hermelinda Linda series is controversial – traditionally attributed to Óscar González Guerrero, but in a different publication to José Cabezas García. The actual comic itself began under the title “Brujerias” (Witchcraft) and was re-named to sell better to its superstitious audience.

The character of Hermelinda Linda is a vulgar looking witch who uses her sorcery to achieve the desires of her clients and herself. She has the ability to change into beautiful women, animals, anything with her potions, and uses her gifts to do odd jobs for others that come to her. The comic relies heavily on dark comedy, macabre, and mischief – jokes between the heinous Hermalinda Linda and beautiful women, and double entendre jokes. Below are some frames from the movie.

This is great Gloria. Thanks for sharing

thanks Caleb!

This was awesome. Great insight. My dad said he read comics as a kid in Mexico. It’s great to see what he could have been looking at. He never recalled the exact names of them as it was years ago. As for my Mom she always mentions Memín Pinguín as a one she read, but I can see how that one can be difficult to discuss. Well, great post!

Will, yeah haha my friend (born & raised in Mx, DF) her fave comic is Memin Pingiun and even for her it has been a difficult comic to defend against american and mexican opinion alike, there are a bunch I didn’t mention, I just stuck with these few. Theres this really expensive book (140.00) floating around called “Not just for Children: The Mexican Comic Book in the Late 1960’s and 1970’s”, if you really wanted to do more research! ~anyway thanks for the response.