Juan FernándezAugust 24, 2016los Cómics / Scene ReportsThis guest post comes to us from Laura Andrea Garzón Garavito in Colombia

Every time I walk into a bookstore I try to check for the comics and graphic novel section. It might not be surprising given that in countries with a comic strip tradition, like the United States or France, there are bookstores entirely devoted to selling such products. In Latin America, places like Mexico and Argentina have given comics an important space among other literature, having both been large scale national creators and international translators of comics. Nevertheless, in many other Latin American countries comics and graphic novels are only just starting to be of common interest for publishers.

Take Colombia, for example. Until not long ago, you could only find translations from mainstream comics, such as superhero ones by Marvel or DC, magazines brought from the above mentioned Mexico or Argentina, and sections in the newspaper devoted to translations of comics such as Calvin and Hobbes or Mafalda (an argentinian political cartoon icon). But there was not much regarding local production in Colombia. Until now.

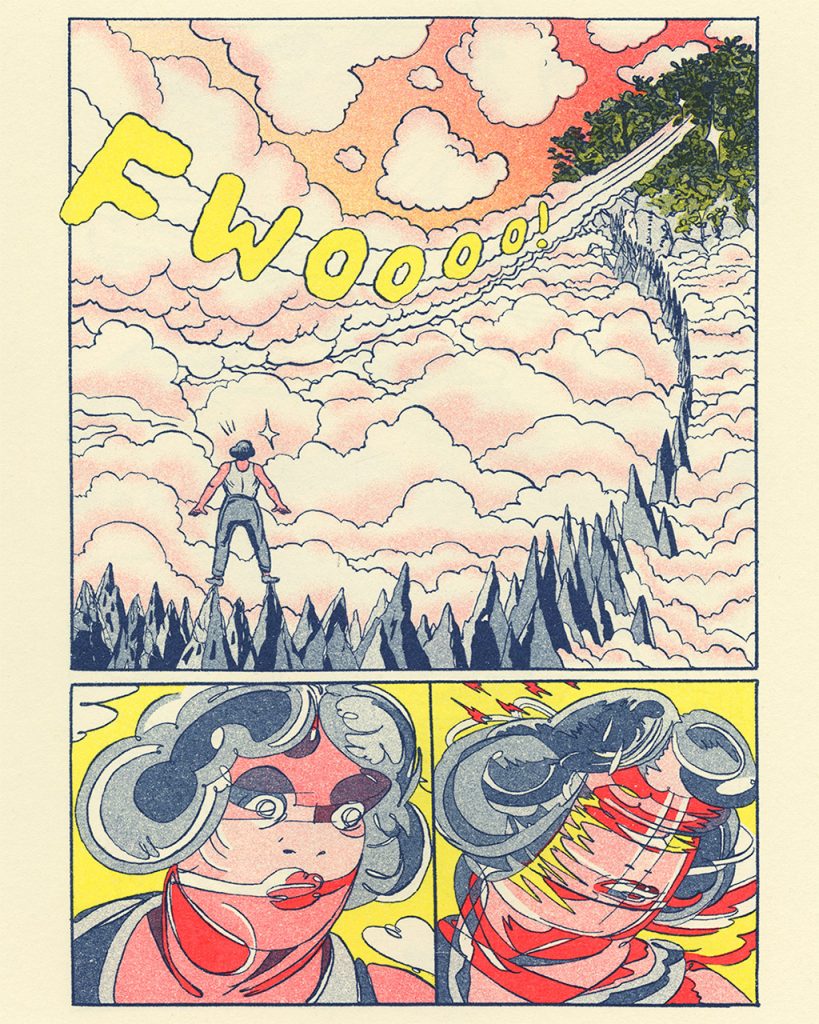

These days, in 2016, as I find so many new books, I feel glad this medium has started to find increased interest among readers. And since we have been building our very own national comics tradition, we have been looking to be eclectic in our selections. I find it interesting that the bookstores that have invested in bringing comics closer to the audience in Colombia, which is my case, have chosen authors with alternative works, who do not necessarily respond to the mainstream view of what comics “are”. That might be because this audience is still forming a definition of what comics can be and their readers enter this universe new eyes. In each comic book club I have been in, I have heard the speakers trying to broaden the perspectives of what such a medium can offer, and the relation that it has with other arts, like film, literature, poetry, painting, etc…

An important part of expanding the national understanding of the many forms that comics take to have Maus in a shop window, side by side with El Eternauta, but is not enough. You might laugh at that, since Maus has been circulating for so long it seems impossible not have bumped into it. But I often think we are, in our very own parallel reality, in a point, similar to the one Spiegelman found himself when winning the pulitzer prize in 1992: where should we place this type of creations? where do we sell these works?

Gary Groth, editor of Fantagraphics, publisher and critic, said in a conference held in Bogotá last year, he felt Colombia’s panorama looked pretty similar to the one he had seen in the United States in the 80’s, which was a time for alternate exploration of both markets and formats. That means thinking comics through various lenses, thinking audiences can be broader than imagined, not only kids or old-time series followers, but a whole spectrum of different ages, backgrounds, genders, and so on. In this scenario, underground comix hadn’t even seen Maus yet! Just like it happened here!

For a long time creators, fans and editors had to research their sources for comics elsewhere, either traveling or ordering books, or maybe being able to find some online version of them. That network has enabled relationships between latin american authors in different regions. Communication through the internet has been a way of supplying for the gatherings: it has built a new kindof dialogue around the comics world. It has also made it possible to think of self-publishing in a different way. Circulation for your work has not been limited solely to printed fanzines but also from web-comics. What we have been seeing in Colombia has been a period of transition in which the alternatives avenues for creativity intertwine, giving artists chances of mixing them and creating hybrid works.

However, the fact that the definition of what comics are and what they can do is a definition in construction means that the medium is till fight for legitimization. A fight to make comics be seem as a viable medium, not classified as secondary, as less than other types of narrative forms, or framed as for only some type of audiences (by editorials or entities in charge of financing new authors and their projects). It also means that there is a fight to find assure that there are market willings to support the production of comic books in Latin America. The very idea of trusting that this kind of publishing can be supported on a national level may be difficult from country to country. What might be easy for Brazil can be difficult in Peru or Colombia.

Now, relations between Latin American countries can help to understand there is indeed viable market for comic books, but, according to Colombian comics critic, script writer and comics editor, Pablo Guerra, Latin America has always been an island in editorial terms. That’s to say Latin American countries have found it difficult to establish connections (even when it comes to traditional forms of literature) between themselves to develop strategies for mutual support, so they do not continue to be regarded as an appendix of Spain, as is done in other international contexts.

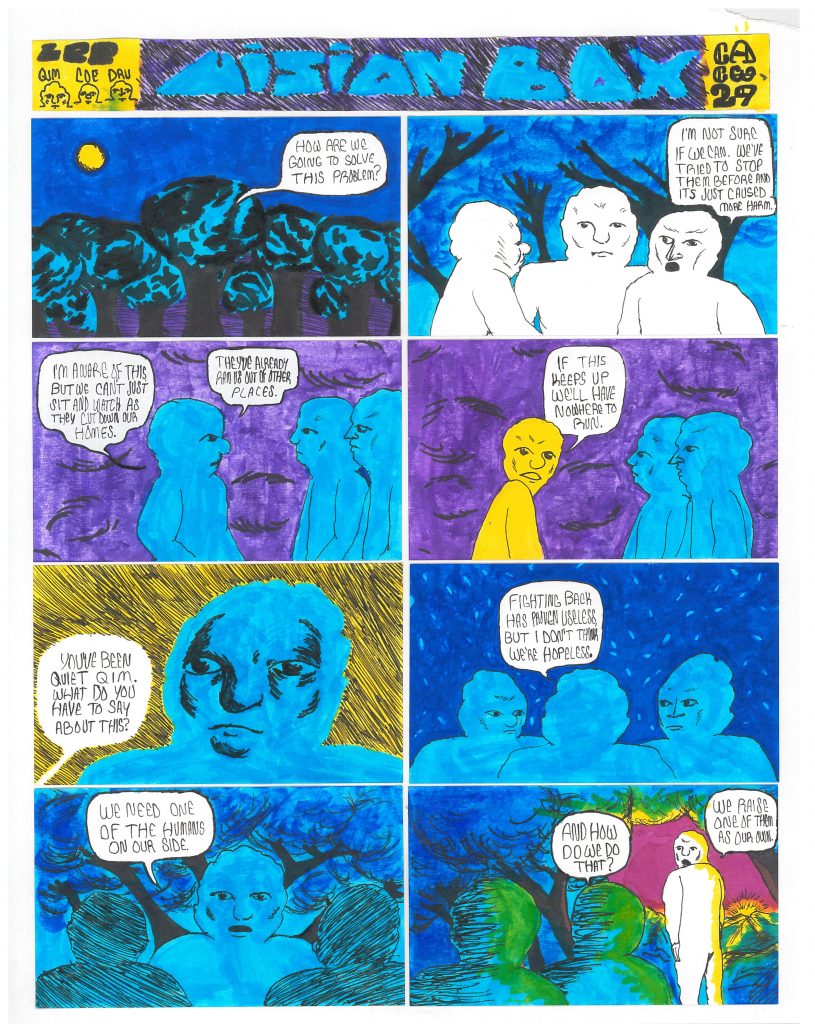

On the bright side of such situation Daniel Jiménez (editor, cultural manager and director of the colombian comics festival Entreviñetas) notes that there is a healthy situation in the panaroma of Colombian comics: a new generation of cartoonists under 35 years of age. They are a group of hungry creators with a network of interesting cultural and artistic production in the comics medium. They understand that they need to be in dialogue with other cultural traditions, perspectives and tendencies happening in other places around both Latin America and the world. They are critical, they question their reality, they aim to create a dialogue through their work. Latin American artists work in and from the interstitial space between center and periphery, and that is reflected in their production. The fact that there is a young generation also makes it possible for relations around this new forms of making comics to be fresh and non-hierarchical. The idea is that among this demagraphic, it doesn’t matter where you come from but rather what you do and how you do it in comics, along with how you participate of the new channels of distribution.

Here is a list of recommendations and highlights of the contemporary Latin American comics situation (Special thanks to Kelly Moctezuma, a young artist, editor and comics curator, for helping me out with this last section so you, dear reader, can enjoy the best of what we’ve got to offer):

Hands up for the editorials publishing comic books and graphic novels. Graphic novels might be a difficult format for new readers, as a broad part of Latin American audience can be, as well as an expensive one, but editorials have found their way around this problem: Rey Naranjo and the recently launched Cohete Comics, part of Laguna Libros, and La Silueta in Colombia, Contracultura and Pictorama in Perú, Catalonia in Chile, La Ñatita in Bolivia, MINO in Brazil.

Some kick-ass girls worth watching for that still struggle to make a living out of this like PowerPaola, Delius, Sole Otero, Isol, Inechi, Maco, Marcela Trujillo, No Sofía, María Luque, CatalinaBu, Juana Medina.

Now some boys worth checking out (I mean, their work) like Luis Echavarría, Fabio Zimbres, Rodrigo de la Hoz, Camilo Aguirre, Henry Díaz, Alejandro Henao, Antolín Olguiatti, Jim Pluk, Joni b, Truchafrita, Pedro Mancini, Jesús Cossio, Marco Tóxico, Eduardo Yaguas.

Publications that have (or had) underlined comics in Latin America are alive and growing: Revista Larva, Carboncito, Entreviñetas (which is a section in the national colombian newspaper El Espectador), Dr. Fausto, Graffiti 76% quadrinhos, Gringo Muerto.

– Laura Andrea Garzón Garavito

Share this page: [...]