Reviewed by Bill Boichel.

Over the past decade, probably the single biggest frustration we’ve experienced here at The Copacetic Comics Company was the inability to offer customers the opportunity to experience the magic of Carl Barks in book form. This frustration was then exponentially magnified by the fact that at any given moment, nearly the entire body of work of the comics creator who was measurably the most widely read and consistently beloved in the history of American comic books was out of print! The influence on American culture of the Disney duck comic books Carl Barks wrote, penciled, inked and lettered for roughly a quarter century is incalculably large. George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are just two of the literally millions of baby-boomers who grew up reading the comics of Carl Barks and who felt the imprint of Barks’s wide-ranging spirit of adventure and pomposity-puncturing sense of humor; R. Crumb’s entire sensibility is grounded in Barks; and this is just the tiniest tip of the iceberg.

Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories was by far the best selling comic book of all time: it’s circulation (sales per issue) in the early fifties, before the dawn of the age of television, was in the millions. Practically every single home in America with children – and many without, as well – had at least one issue at any given time, not to mention every barber shop and doctor’s and dentist’s waiting room. And the lead off story in every issue, the main attraction, the work every kid (and adult) read first, was a Donald Duck 10-pager, almost invariably by Carl Barks. Thus, an entire generation spent millions upon millions of hours reading works that were both wildly entertaining and subtly subversive. While it is certainly difficult if not impossible to quantify the influence these comics had on the generation that came of age in the 60s, there is no doubt that this influence was very real, and the life and works of Robert Crumb stand as Exhibit A.

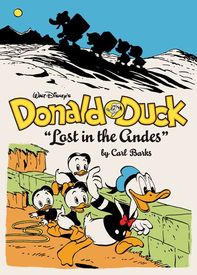

Carl Barks is one of the true titans of comic books, one of the very few who can hold their own with the likes of Jack Kirby, Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman and R. Crumb. His fluid cartooning and storytelling is simply unmatched. His complete mastery of facial expression and body language, combined with a hugely insightful understanding of American society and culture that was the fruit of his twenty years spent in the American labor force prior to entering into his cartooning career, make Barks a wholly unique and massively influential figure whose importance as an artist transcends even his amazing level of popularity. Now, at last, well over a decade since Gladstone Publishing’s incarnation of the Barks oeuvre went out of print, his collected works will once again become available for North American readers (his works have been in print in parts of Europe; elsewhere?) in what – based on the evidence of the first volume – is sure to be the most outstanding edition ever produced. Rather than potentially put off novice Barks readers by starting the series right at the 1942 beginning of Barks’s tenure on Donald Duck, Fantagraphics has launched the series with a period that is both one of the most popular and critically heralded (think Duke Ellington’s Blanton-Webster era band): the stretch in 1948 and 1949 that contains this volume’s “title track,” Lost in the Andes, as well as the equally classic March of Comics giveaway, Race to the South Seas, along with two other “feature length” tales, nine consecutive (and classic) 10-pagers, and a sizable helping of one-page gag strips, which, taken together, give a good idea of the tremendous range and quality of his work. An eight page introduction by Donald Ault, one of the foremost North American Barks authorities, starts off the collection, and it concludes with twenty pages of notes on the stories by a bevy of Barks scholars from around the world, including The Comics Journal’s Rich Kreiner.

No one ever skewered American global hegemony and the capitalist system that powered it – and played it all for laughs – quite like Carl Barks*. Barks’s most famous creation, Uncle Scrooge, was presented as the soul of the Anglo-American ethos (note the initials: U.S.), and Barks clearly relished pointing out its blemishes and found absurdity at its core: in the form of Uncle Scrooge’s money bin, which, despite being filled with a “fantasticajillion” dollars, it was Scrooge’s sole passion to fill ever higher, and sole pleasure to literally swim through the cash. For example, in the classic ten-pager contained in this volume, “The Sunken Yacht,” (more about which later), it is demonstrated that it is simply impossible for Donald Duck to get ahead in his entrepreneurial enterprise of marine salvage, as not only is Uncle Scrooge the only source of significant income for him, but literally every resource that he needs to carry out his work is also owned by Uncle Scrooge, who deliberately fixes the prices to ensure that the entirety of the fee he pays Donald is recouped by these businesses he owns, resulting in Scrooge getting Donald to do his work at essentially no cost to himself and no benefit for Donald. This 1949 view of capitalism as a game that is rigged to benefit only the hegemonic owners of capital would jibe nicely with the world view of Occupy Wall Street today! Although, it must be said that in his later years, as the culture changed during the 1960s, Barks began to gradually identify with Uncle Scrooge and became noticeably less critical of him and increasingly skeptical of the common culture that he formerly embraced; but such is the arc of life, and this is no way diminishes the effectiveness and importance of his early critiques; and what’s more, it was as Barks began to soften his stance that Crumb began making his epochal comics that were filled with Barks-inspired attacks on the status quo – the torch had been successfully passed to the next generation.

Those tales that take the duck into the “third world”, or “the south” of global development parlance, certainly share the perspectives generally held by his contemporaneous audience, and so unsurprisingly take as a given the then current perception of the natural superiority of the American way – yet it was precisely this self-satisfied smugness that was so often the target of Barks’s barbs. This is particularly true in this volume’s most famous story, the titular “Lost in the Andes,” in which the various hierarchies continually show a disrespect for those who end up actually doing the labor as a result of upper level abdications that in turn result in the devolution of responsibilities to the lowest levels. Yet, again, it is in his bald confrontation of US attitudes embodied in the behavior of Uncle Scrooge that Barks is most effective in delivering his criticisms. Take this volume’s final full-length tale, “Voodoo Hoodoo,” for example. Here Donald is hit with a voodoo curse that was intended for Uncle Scrooge. Thus, starting out the tale, we have a relatively (but, certainly, as the story goes on to point out, not completely) innocent bystander paying the price for the capitalist’s transgressions, and, to compound matters, Scrooge finds the irony hilarious and has a good laugh at Donald’s expense – what a guy! When Donald asks for the motivation behind the vengeful curse he was the mistaken recipient of, Scrooge doesn’t beat around the bush and explains: “My eye fell on some wonderful land in Africa that I wanted for a rubber plantation! The owners were a tribe of ferocious savages that believed their voodoo gods prized the ground! They wouldn’t sell, so I hired a mob of thugs and chased the tribe into the jungle! I got the land, but boy, those savages were mad! Their witch doctor hoodooed and voodooed for weeks! I woulda been shrunk if they’d gotten a hold of me! But I outsmarted ’em!”

The above can be divided neatly into two: 1) The description of Scrooge’s actions, and 2) his justification of them through his ideologically loaded definition of the victims:

1) – “My eye fell on some wonderful land in Africa that I wanted for a rubber plantation! The owners (…) wouldn’t sell, so I hired a mob of thugs and chased the tribe into the jungle! I got the land,(…) I outsmarted ’em!”

2) – ( were a tribe of ferocious savages that believed their voodoo gods prized the ground!) (but boy, those savages were mad! Their witch doctor hoodooed and voodooed for weeks! I woulda been shrunk if they’d gotten a hold of me!)

This is as neat and precise a definition of colonialist attitudes and methods as you are likely to find!

And, while we’re on the subject of “Voodoo Hoodoo,” it must be said that many will find themselves taking exception to some of the racial caricatures on display here. This is, of course, entirely understandable and generally commendable, as it represents an acknowledgment of the harmful effects of uncritical acceptance of ideologically loaded representations designed to denigrate and devalue. It must be stated however, that a wholesale rejection of any and all works incorporating outdated racial representations will result in the abandonment of a rich vein of American history and popular culture and a gross distortion of American identity. This is far too broad and complex an issue to tackle in this review, but certainly racial caricatures have a long history in comics and are an inextricable part of American visual culture. In addition, an argument can be made that funny animal comics were an important early avenue through which narratives, themes and concepts derived from African and American Indian traditions, as well as coded representations of American racial conflicts, penetrated American popular culture. If there is a founding father of the funny animal genre, it has to be George Herriman, who, in addition to creating the primal dyad of Krazy and Ignatz, penned an entire menagerie of cartoon animals that served as the supporting cast, derived many a tale from African and American Indian folk traditions, and who was a Creole born in New Orleans who had European and African forebears; Krazy can quite productively be read as a cypher for the black experience in white America, of tremendous resilience in the face of perpetual persecution, of maintaining a joyful outlook where sorrow would be expected – a prodigous contribution to American Arts and Letters and a generous gift to the American spirit. An example of how the roots of American popular culture are hidden in racial caricature can be made with the most famous of them all, Mickey Mouse. Many have noted that Mickey’s visual origins are to a large degree simply a clever makeover of Felix the Cat (who was the first international animated cartoon celebrity): that by substituting round mouse ears for pointed cat ears and adding sound, Mickey effectively softened Felix’s rough edges and made him sing; but it is less well known that Felix the Cat has his roots in the comic strip Sambo and His Funny Noises. Upon the death of Sambo’s creator, William Marriner, in 1914, Marriner’s assistant, Pat Sullivan, moved on to establish an animation studio, the inital productions of which were nine Sammy Johnsin cartoons. Sammy was, for all intents and pursposes, simply Sambo with a new name. By the end of the decade – during which time Herriman’s Krazy Kat had earned wide acclaim – Sullivan, with the able assist of Otto Messmer, had moved on to create Felix the Cat, whose antics and storylines were often recycled from Sambo and Sammy. (Gordon, Ian. Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 1890 –1945. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998: 67-75) In other words, Mickey Mouse – and hence, to a degree, the entire Walt Disney media empire – has direct, but unacknowledged, roots in Little Black Sambo (which was, of course, not American in origin, but was rather the creation of a Scottish woman, Helen Bannerman, living in India and originally depicted a child of Tamil, not African, heritage; it’s a tangled, knotty root, indeed). Bugs Bunny is descended from fellow “trickster” figure Br’er Rabbit, and his crazy rivalry with Elmer Fudd represents the unconscious racial conflicts running through the American national identity at the time, with a manic edge that befits the necessary repressions and elisions that were keeping the underlying reality hidden. Thus, the Time-Warner empire, too, has roots in racinated folk culture. Which brings us to Carl Barks. In “Voodoo Hoodoo” we do, of course, have racial caricatures. First and foremost we have white, “vanilla” Americans depicted as white ducks, which is certainly a caricature – whether or not it has a racial dimension is open to debate (is Daffy Duck black? some say yes) – but one that is so ingrained as, fascinatingly, to be all but invisible. Next, we have Bip Bop, a character that is coded as an African American jazz musician who makes a brief appearance at the outset as the person who Donald seeks out as a likely being the best source of the straight dope on the supposed zombie that he has heard about. Bip Bop is depicted as bear-like and coded as black primarily by his dialect-ish dialogue, and secondarily by his name and the visual that he is carrying a trumpet – additionally indicating to readers that he is part of the jazz subculture – which then cues the relatively subtle use of racial caricature conventions incorporated into his representation. Next up we have the story’s central and unifying character, Bombie the Zombie. Bombie, it turns out, is – while clearly represented as being of African origin – not much of a caricature, actually. He is by far the most realistically delineated character in the entire story, and, ironically, one of the most human depictions in the entire Barks oeuvre: he has a human head, human arms and legs, human hair, human ears and nose, and a human mouth that, significantly, does not display the impossibly oversize lips so closely associated with blackface caricature; in fact, he has a complete lack of animal characteristics that is quite rare in Barks, and which clearly indicates his sympathy for the character, and which allows (encourages?) the possibility of a stronger reader identification as a result. When the action moves to Africa, the depiction of the natives is clearly problematic as it visually reinforces Uncle Scrooge’s verbal definition of them as “savages” (the pointed teeth is a dead giveaway) and thus initially encourages readers to embrace Scrooge’s ideological position that their exploitation is justified. However, importantly, as the story progresses, it is revealed that the value system of the “savages” is, at its core, identical with that of Uncle Scrooge – namely that money is the most important thing. Thus, the narrative reveals that the conflict is not, as it originally appeared, one of a clash of civilizations, of a “civilized” us and a “savage” them, but rather a straight forward competition over the control of resources and the value they represent, that is waged via duelling systems – Uncle Scrooge’s capitalism on the one hand, and Foola Zoola’s voodoo, on the other. A conflict which Donald and his nephews find themselves caught in the middle of, and the ultimate victim of which is that most human of all the characters, Bombie the Zombie.

These digressions have taken us away from the core appeal of Barks, and that is found more than anywhere else in the hi-jinx, slapstick humor of his aforementioned ten-pagers that appeared almost every month in nearly every issue of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories for over twenty years. Barks explored many themes over these two-hundred and fifty odd stories, among them mastery, maleness and competition (often with Gladstone Gander), the search for success and the often inevitable failure, the challenges of nature, the hypocrisies of society, the mating game (with Daisy usually somewhere in the mix), the cost of vanity, the value of family, the mechanics of capitalism (usually involving Uncle Scrooge in some capacity), the promises and perils of technology (usually employing a guest appearance by Gyro Gearloose), and many, many others. Nobody ever did screwball comedy in comics (or anywhere else, for that matter) like Carl Barks. When it comes to disaster as comic dénouement, he pretty much wrote the book. His genius as an artist and writer is best fulfilled in these ten-pagers, which taken together truly fulfill the definition(s) of classic and for all intents and purposes constitute a unique comics form all of their own: there is simply nothing that compares to them. The nine ten-pagers in this volume are prime examples, every single one a joy to behold.

The sole quibble we have with this volume is that of a missed opportunity in the story notes. The aforementioned story, “The Sunken Yacht” has a unique fame in the Barks oeuvre (and is certainly a feather in the cap of the comics medium as a whole, as well) as a result of it containing the invention of a method for raising a sunken ship — filling it with ping pong balls, believe it or not – that was actually successfully employed fifteen years later in the raising of a ship sunk in Kuwait, and resulted in the patent application for this method being turned down in Holland due to someone in the patent office being familiar with the story (those Dutch know their comics) and thus overturning the application on the grounds of prior publication. This anecdote is well known among Barks aficionados, so it was surprising that it was left out of the notes! At least Copacetic customers need not be left in the dark on this particular Barks legend. Read more, here.

The Fantagraphics edition of The Carl Barks Library is ideal in almost every way and is sure to be the definitive edition of the works of this great comics master. So, thank you Gary Groth, Kim Thompson and Eric Reynolds, for undertaking to edit and publish the The Carl Barks Library. Thank you Jacob Covey and Tony Ong, for your excellent design. Thank you Rich Tommaso and Paul Baresh, for, respectively, your superb coloring and production. Thank you Donald Ault and the host of other fine Barks scholars for your thoughtful contributions to aid in the understanding of and provide context for the work presented here. And, of course, most of all, thank you Carl Barks for producing one of the greatest bodies of work in the history of comics. Doubters among you may want to take a moment to read this generous 17-page PDF preview, but bear in mind that the experience simply won’t be nearly as satisfying as that provided by the print edition.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

* Except for perhaps his greatest disciple, Robert Crumb, who clearly picked up on exactly this element and brought it to the forefront of his 1960s comics; and also, although to a diminishing degree, to his later humorous works as well, all of which still contain a distinct Barksian flavor.

– See more at: http://copaceticcomics.com/comics/donald-duck-lost-in-the-andes#sthash.Wtv7dju5.dpuf