Moore/Mendes; Drnaso & Kupperman; Regé, Jr.

—————————————————————————————————

Understanding Detroit: The Nonfiction Work of Anne Elizabeth Moore & Melissa Mendes

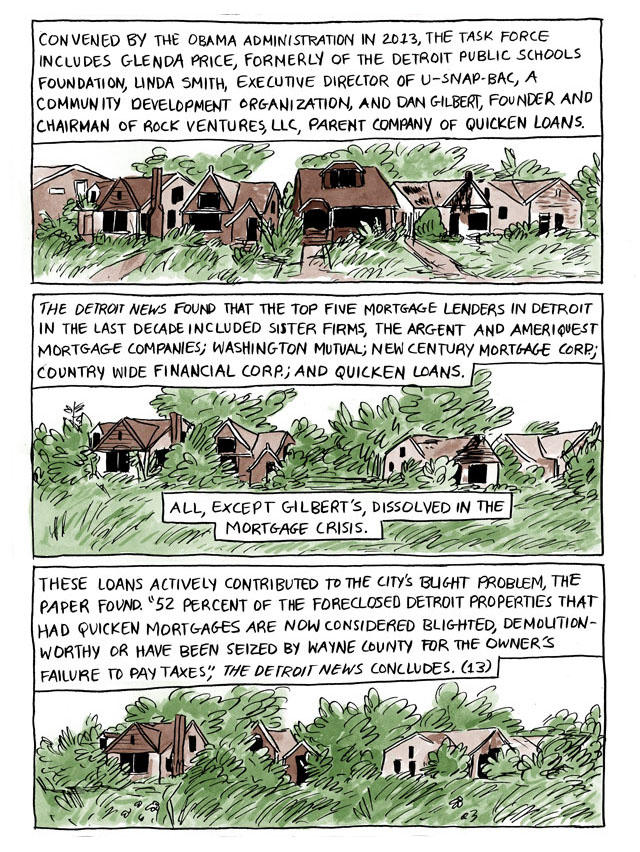

Sally linked to this last Friday, Alex Dueben’s interview with Anne Elizabeth Moore and Melissa Mendes, about their collaborative non-fiction comics:

What do you two think comics can do that an essay or report couldn’t?

Moore: This is a question I get a lot, since I’ve done both text-only reporting and comics journalism. There’s a particular story in Threadbare I did with Julia Gfrörer called “Let’s Go Shopping,” about fast fashion retail work. I went into a local H&M—it was years ago, now, so that worker’s not there anymore—and started chatting with one of the retail workers. Now, like factory workers, and many many other workers along the entire garment production and display assembly line, retail workers for most fast fashion outlets sign non-disclosure agreements stating that they agree that they have the right to be fired if they share information about their benefits or wages. This is a nutso clause in any contract designed to keep people from sharing information and organizing to improve their lives, and it’s basically a knife wound to the project of basic democracy, since it means that even though a LOT of people work in the garment industry, few people talk about what it’s like and so, for example, reporters usually struggle to write about it because no one will go on record.

But no one knows, or cares, what comics journalism is, so I walked into this H&M and was like, “Yeah we draw this thing and it works like this and I do need a photo for reference but we can hide your identity to protect you and if you want we can draw you in your favorite outfit even if you aren’t wearing it right now, I just need to ask you a few questions that are in complete violation of your NDA are you OK with that?” And she answered everything I asked. Because with comics we were able to protect her, but also depict her in an interesting way, and she was invested in contributing to something she would be excited about. (That Julia drew it was super helpful. She is very very popular with models and fast fashion workers.)

That’s an actual example of information that wouldn’t have been accessible without the form of comics. In “Scenes from the Foreclosure Crisis,” Melissa and I were able to do a very similar thing, depict a nonbinary figure, who still has a very clear personality, history, and set of concerns, in a way that wouldn’t bring them undue attention or frustration. Or violence, to be frank. (Detroit is very conservative, actually, so that’s a concern.) In text-based journalism, you’d have to give some kind of identifying distinction, and almost anything I could think of in this case would put my source in danger.

Also audience, of course: comics journalism is read by a far less newsy crowd. More young people. I hear from a lot of students that this was sort of their gateway drug to text-based journalism. But it takes a long time, so you have to plan it all carefully.

Mendes: Whenever I get this question I always think of Joe Sacco. There’s no way his work (Palestine, The Fixer, etc.) could ever be anything other than a comic. He’s going into these terrifying places, these war zones, and instead of just taking photos, which can be sort of voyeuristic, he’s drawing. There’s no question that it’s through his lens, that it’s his own point of view– he’s making those marks on the paper. There’s no way it could be taken as objective, while it’s possible to write or photograph or record in such a way that you forget there’s a person behind the camera or the keyboard. (I’m sure there are smarter words for what I’m trying to say but I haven’t written a college paper in like fourteen years so…) Does that make sense? Sacco is reporting, but it’s personal, and you feel that as a reader. You can’t escape it, it’s more raw somehow. The handmade aspect of cartooning makes it more human, and we are still able to protect identities, like Anne was saying.

—————————————————————————————————

Can You Illustrate Emotional Absence?

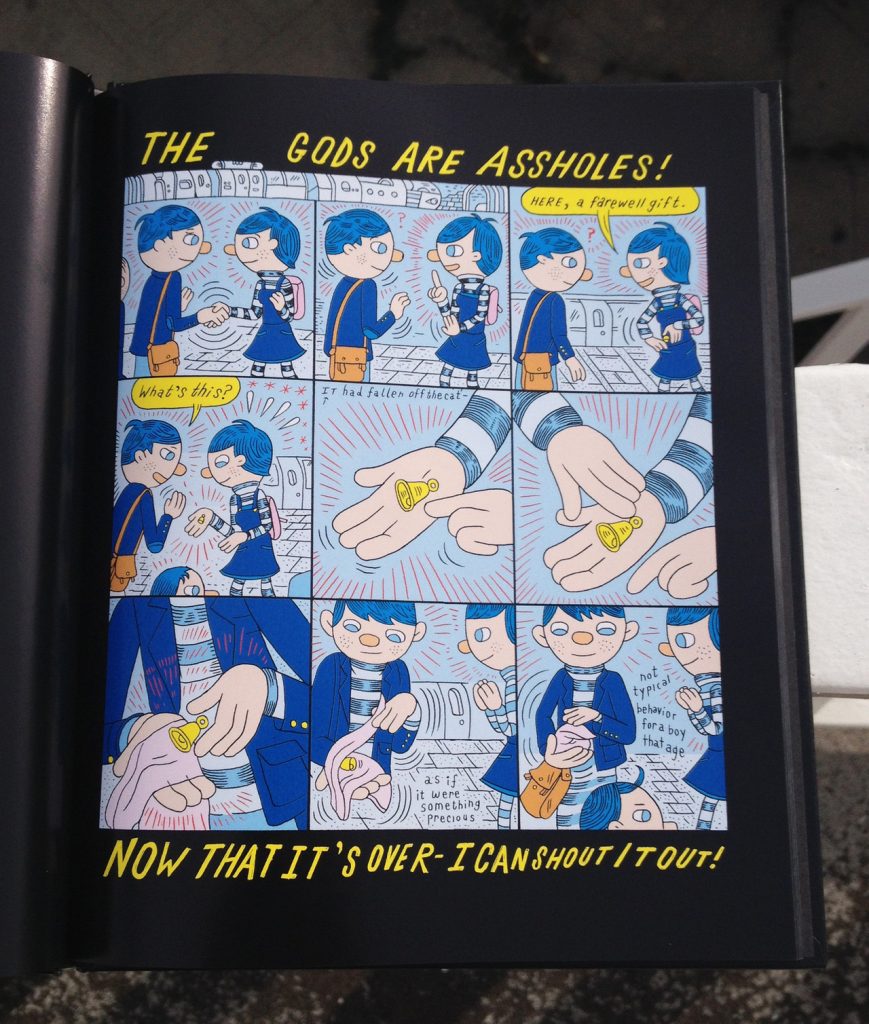

Ed Park looks at recent work by Nick Drnaso and Michael Kupperman:

RE Drnaso:

With his fluid framing — fitting anywhere from two to 24 panels to a page — he dictates information delivery, allowing the mind to breathe. His drawing style is at once poetically attuned to details of neighborhoods and interiors (the lit canopy of a gas station at night, the banquette at an antiseptic diner) and deceptively plain when it comes to the people who inhabit them.

RE Kupperman:

For an artist known for his off-kilter tableaus, this book has a static look, especially in its rendering of boldfaced names from the past. More problematic are the gaps: mysteries unsolved, re-creations that collapse under the weight of a disclaimer. Of a 1943 meeting between Joel and Henry Ford (once a vocal anti-Semite), Kupperman wonders, “What did they think of each other? There’s no way of knowing.”

—————————————————————————————————

—————————————————————————————————

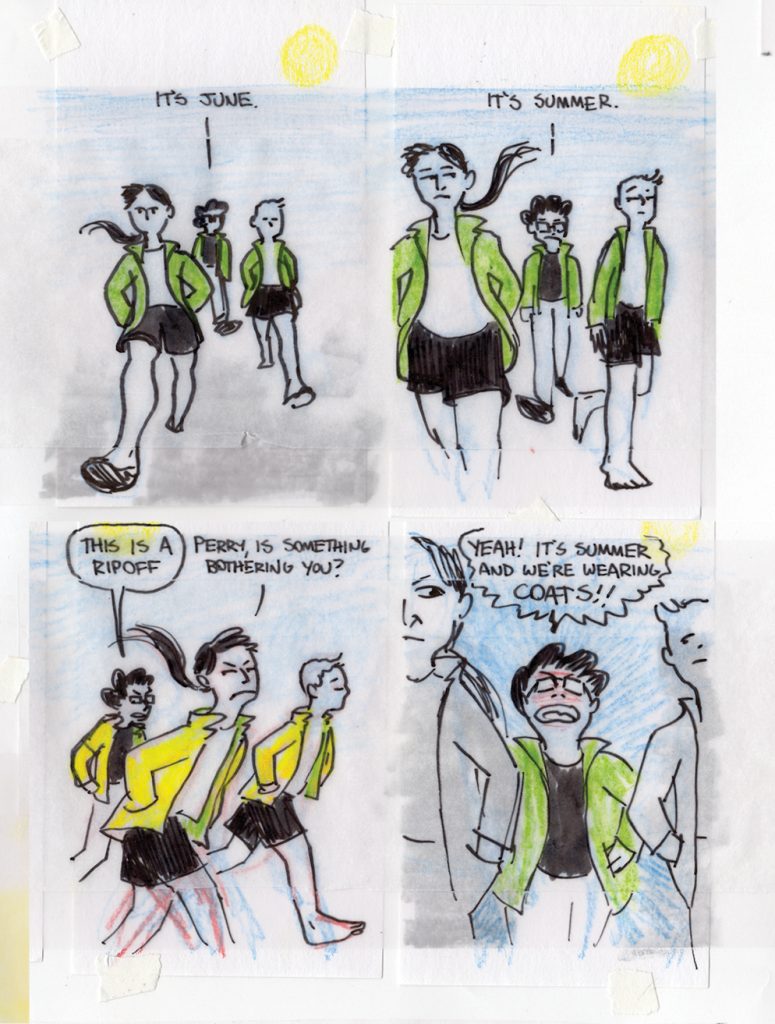

Joanie and Jordie – 6-12-18 – by Caleb Orecchio

—————————————————————————————————