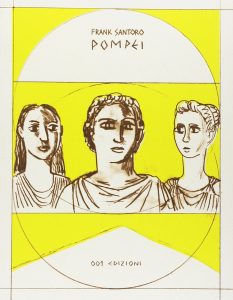

Daniele Barbieri‘s review of Pompei by Frank Santoro (001 Edizioni, 2018) was originally published on Fumettologica on May 5th 2018. You can read the Italian review HERE.

Valerio Stivè, who translated Frank Santoro’s Pompeii (PictureBox, 2013) into Italian for 001 Edizioni, kindly translates Barbieri’s review into English for us below (with sections in bold retained from Barbieri’s original piece).

The idea of narrating a historic event through the personal events of a single fictional character in order to let the reader/spectator empathize with the story and understand the events – then comprehending History in a much deeper way than reading a History book – is not new. In literary fiction, as well as in cinema and comics, that is a common and effective narrative device, as long as the reader is able to understand it. Our present times can become the present of those events (despite the historical and cultural differences); and an every day life that we recognize as familiar suddenly fades into something totally different: the historic event itself.

If limited to this, Pompeii by Frank Santoro could be seen as a story like many others, maybe more delicate and emotive. Yet there already are so many tales of the last days of Pompeii, even similar to this…

The thing is that there is so much more in here. From the very first pages, even before one could figure out where the story would go, the drawing looks rapid, approximative; almost like a sketch or a storyboard – where the imperfect lines are not erased, but adjusted, leaving the imperfection in plain site. No colours, obviously, just some quick textures for the shadows, with an overall sense of temporariness and instability.

Then, the story starts to take shape: Marcus, the main character, is an assistant to a painter who is probably going to become famous and move to Rome. Marcus prepares his colours and helps him with the paintings, while forced to be complicit in the painter’s affair with a princess, that needs to be kept hidden from Alba, his suspicious partner. Marcus has a woman too, Lucia, with whom he left Paestum, where he has no intention to come back: he wants to become a portrait painter in Pompeii – just like his master – to make money and start a family with Lucia.

This is the picture of everyday affections and little tensions on which the eruption of the Vesuvius occurs. Obviously, the event leaves everyone astonished. However, Marcus encourages the painter to draw that shocking event right away (while it still has to fully take place). “You can add it to the landscape commission! You’ll be the first to paint the gods in action!” he says. The idea of drawing, which was there since the beginning of the story – but, before this, only in the work of the painter – now becomes more and more relevant.

The drawing itself is a proof of events, and at the same time, it is an expression of those emotions that the events can raise; and again, it is also a performance, a way to humanize natural elements – and to humanize means having some sort of control over things, or at least the illusion of having it. That would imply leaving a recognizable mark, which maybe – as in Pompeii – can survive centuries, bringing traces of that distant world to a totally different world.

However, Santoro’s graphic novel is not just this – a beautiful story of everyday affections set in Pompeii. There is also an implicit and an explicit reflection on the act of drawing and its role. I don’t know, and we cannot know for sure (and we probably cannot fully trust the statements of the artist) if these drawings are the result of full improvisation, as it happens with sketches (works that are meant to be tools for the artist only, and will never be shown to the public eye), or if they are rather the result of a designed construction made to produce the effect of improvisation.

The method is designed, that is for sure; as designed as the story. Although the drawings have the same effect of the quick movement that comes with the realization of an idea or of the sensation you want to commit to paper, when the most important thing is to secure an intuition, rather than obtain an exact representation. Usually, there is always time to fix each single shape.

There is a famous case in the history of Art. Look at Antonio Canova’s statues: their extraordinary elegance and expressiveness are balanced by a firm classicism; which is the price Canova pays to the inclinations of his time – a time when it was important to create visual art that was meant to be in contrast to the frivolousness of Rococo. It is true that the immobility of his figures is balanced by a dynamic tension that often makes them extraordinary; but that does not make them less immobile, nor less icily, neoclassically statuesque, and monumental.

Now look at Canova’s sketches. Small objects with a very rough modeling, definitely at the antipodes of the clarity of marble statues. They are made of clay or chalk, allowing us see the tracing of the hand or of the instrument that shaped the matter: we can sense the afterthoughts. Those are private objects, attempts carried out on the wave of inspiration – which then gave life only occasionally to a definitive work, that in the end may appear so much different from its sketch.

For Canova and his contemporaries, sketches were not meant to get the same consideration as the definitive work. Those were private exercises. Yet, after his death, during the Romanticism, the dominant poetics of inspiration and improvisation lead the nineteenth century critics to consider those sketches as the master’s most successful works. Critics were wrong, that’s for sure, because those were not – and cannot be – Canova’s actual works. Yet the mistake brought an important intuition, because there was something in those extemporaneous attempts that went missing in the definitive piece, with all its perfection.

Improvising is not easy: a jazz musician must have acquired an extraordinary familiarity with his instrument and with the phrasing of the genres in which to engage. And sometimes, in spite of this, improvisation can lead to repeat well known schemes and phrases, on which the hands easily rests. But when the improviser is really capable of following the inspiration of the moment, what he produces is unlike anything you could read on a score. I don’t mean that the improvised work is always better than that designed one, but neither the other way around; and each of those has its own peculiarities. Then, we cannot do without improvised works or without designed works, and today we enjoy both the sketches and the completed statues of Canova (even if he wouldn’t agree).

With Pompeii, Frank Santoro built a eulogy for drawing, for sketching, and for the “bozzetto”. Emblematically, as the reader would find out, what will survive in Pompeii are not the master’s meditated works, but the scribbles on the wall of his assistant, improvised, approximate, yet inevitably charged with all the emotions of the moment. – Daniele Barbieri, for Fumettologica May 2018