QUESTIONS is an anonymously curated column that will appear occasionally on Comics Workbook. It presents articles, interviews, drawings, and more under the rubric of a general theme.

TRANSITION might refer to: changes in the artistic, personal, or professional life of an individual creator; changes in the wider zeitgeist of a medium or industry, which can in turn affect individual works; and of course the implied passage of time from page to page, panel to panel, that is arguably the central characteristic of comics.

TRANSITION features interviews with Cameron Nicholson and Simon Moreton, an article by Kim Jooha, and reviews of work by Warren Craghead, Sarah Ferrick, and Aseyn. Thanks for reading. Thanks to all contributors for their time.

Cameron Nicholson on Becoming Comfortable with Yourself and Your Eyes

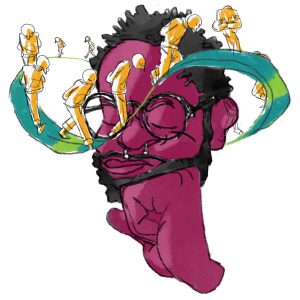

An interview with Cameron Nicholson began by asking him to select two recent illustrations that he’d like to discuss, with the hope of using this as a starting point to understand where Weston sees his work now and where he’d like it to go. Subsequent illustrations were produced specifically for this interview.

QUESTION: Why did you select these pieces? In what ways do you think they’re connected?

Weston: These two piece relate in a way of feeling. I did both of these pieces while drawing in Skype. I won’t talk about “how” I created these pieces but why I did. These two pieces were created because I finally let my mind free from being so scared of mind drawing. In simple terms I actually got REALLY close to drawing what my mind sees.

What comes first for you, the idea/story or the format of a work? How do you think about the connection between those two elements?

This really depends on my current state of mind. If it’s con season (now) format is what I’m always thinking about. Mainly because my ideas fluctuate every single day. Because I’m constantly learning, through literature, videos etc etc. Ideas are constantly generated everyday for me and I tend to write a TON of notes.

“Burgundy” is a good example because it is simultaneously “I want to write poems & I need to make them FEEEEL like a notebook/journal.” But if I’m working in animation or illustration the format comes second, but then again the format alters my ideas. It’s a back and forth action process. If you think about it animation and illustration are such specific languages that you NEEED to learn. And with Burgundy was a mix of languages (illustration and poetry) so I was able to rely on some principles and not all of each. Also saying that, as I get better I will strengthen the foundations of each form of art to increase the quality of my products.

Here’s where it gets interesting, I am conscious of my mind’s creations but the reason why they morph so much is because of the fear of complacency. The fear of “looking” the same in everything I create. The fear of embracing a look and running with it not realizing that’s how you build parts of your foundations (the Latin roots of art). It’s not smoke and mirrors, fear runs through all of us in different ways and those are part of my fears. This may seem like I’m exposing my “secrets” but no, I know for a fact many people feel this way. Being constantly surrounded by great artists and great works can scare you in ways that alter your creations. Sometimes it helps but ultimately it’s been hurting my progress.

But to add I’ve learned how to focus more and just “create” rather than be infatuated with the art around me. I’ve caught myself copying both intentionally and unintentionally. I’ve been able to realize that not being afraid to be “you” is the start. Basically becoming comfortable with yourself and your eyes. Hopefully that doesn’t sound too poetic.

Do you think consciously about carving out time for different kinds of work in your practice, keeping different muscles active? Or do you approach things more intuitively?

Carving out time for different kinds of practices? I do, my days work like a steady tempo that improve on each day. I can’t animate and illustrate in the same day (unless I’m under an intense deadline). So for my personal work I do cater my days to certain skills, but also if the illustration/comic requires another skill I still split it on a separate day. I will say sometimes I do fall into animating something and losing so much time because it’s addicting. And to be honest sometimes I when I create it comes all natural with no schedule (but that’s rare). Thus solidifying my mind jumps to various ways of creation, because there are too many ways to solve “the problem”. Everyday is another verse to the song I call life. Even when my mind tends to lose itself in that song; I can mess up on any key but I have to improvise and keep going.

When you think about your work more generally right now, does anything feel like it’s in transition? Are things evolving? Are things in flux?

I feel things vary for me. I’m not a normal creative, (we all aren’t) what I mean is my mind goes 90 miles per hour ahead, no matter if I tell myself not to. Like even writing this I can’t get away from thinking about projects. But saying that, I am in a big transition of my life. I’ll be honest, I don’t have many people understand me and that scares them to like my works. Or even scares them to try to leap in my mind to try and understand what I’m saying. It’s like I’m speaking a different language, thus language barriers. Earlier I mentioned “the latin roots of art” what I mean by that is “the language of art” = “the basics/foundations of creating/picture making/ etc etc.

How I see art is split up into many languages to create things/ideas. Illustration, printmaking, design, animation, film, coding, woodworking etc etc. each of those things have different terminology that you need to learn to speak/do and understand/understand so you can progress further. It’s like learning English to French, most of the words come from the same Latin root words. I believe every form of art have very similar foundations. Shape, Value, Depth, Rhythm just to name a few. Shape can lead into literal gesture shape of a beautiful piece of carved wood to a marvelously appealing drawing in animation. I use my apple box analogy to fill the gap of understanding.

If you are talking on a stage and you’re too short to reach the podium, you may have to get an apple box to stand on to reach the mic. That apple box are the foundations and you are still you. The apple box isn’t a crutch of your height but it works as an extension of your ability. Thus making you the point of interest once you start speaking. Because what people want to see is YOU! The foundations are there to hold you/ideas up so people can dig the your wild creations.

So I’m at a point in my life where I started to notice less and less people understanding my ideas. Even close friends being very confused at my drawings after working hard to get to the “finished” piece. So I an looking at the languages and learning them to strengthen my ideas and make them so strong people cannot help but to look at my stuff and understand it. You become so good that people can’t ignore how good you are. This goes beyond art but I’m using art as my example. People unintentionally put focuses on you to get and figure out your art path. That makes them comfortable to support you. So that can be very positive or very negative. We only keep progressing if we want to progress and my plan is to keep going. My current goal is to land a job in tv animation and expand further and further. There is no endgame for me but getting that far is only the start.

I also only speak through my eyes. Every person sees differently. Everything I say are my thoughts. I hope to keep becoming a better person/artist so my thoughts are solid and can mean something decades from now.

But to finish the main thing I take from creating is living. You can’t create without living through things, anything, from sipping a great cup of coffee to a crazy flight. Like just the other day I started using make-up YouTube videos to understand the face better, or at least how to use color and mixing to form human skin. Live, love, learn and be the best you can be.

Applied Transition

QUESTION: What can be learned from examining some recent comics in terms of their approach to transition?

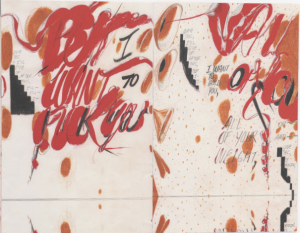

The operative unit, the key transition, in Sarah Ferrick’s Sec is the turn of the page. A distinct visual approach on each spread encourages you to drink it in all at once – words, images, cadence, flow. Words flow laterally across the page. Phrases repeat, or sometimes don’t – a monologue that ebbs and flows. Images refract.

Some pages do have panels, but they are less a literal indication of time passing than an incantation of rhythm, of beat. There’s a sense of accumulating urgency here. Heavy breathing. Phrases punctuated by slashing commas.

And how much time passes between each spread? Sometimes just moments, as phrases occasionally continue from one page to the next. But on the other hand, an eternity could well pass between superficially unconnected thoughts like: “All the heat I could sense from the other side of the room,” and “Now, how does it feel to make something unwanted?” In both cases, though, as the words “one sec” repeat again and again, you begin to feel the ticking of those secs innately. The passage of time. Accelerating desire.

Sentiments of longing explode out of the grid: “But I want to fuck you” – “To put every part of you in my mouth” – “So come here or not.” These billowing words are sometimes difficult to read at first, but the feeling is always clear. Letters in deep red shout out – or are they passionately whispered? – and demand to be heard.

“There is nothing left to say,” the final words in the comic read, “but—”

Is the narrator cut off in a moment of pleasure, or surprise? Or is the work’s final spread, an explosion of flora that recalls those earlier words of red calligraphy, the end of the sentence? Another expression of longing, but this time so deeply felt that it cannot be put into words? Narration transitions into a swell of color, of passion and desire – a conclusion.

In Warren Craghead’s La Grande Guerre, transition occurs as a function of time truly passing, in the most literal sense. Beginning in 2014, Craghead committed to producing near-daily images of the First World War, commemorating with each drawing something that occurred exactly 100 years ago on that day.

Craghead has said the project aim in part to underscore just how much time passes in five years; a point succinctly made through the very fact of the work’s existence, through the accumulation of images. In other words, it’s one thing to measure 1914 – 1918 by mapping it abstractly onto a period in your own life: ages 1-5 or 34-38, for instance. It’s another thing entirely to be reminded each day of a war plodding forward, or indeed to forget about the project for months (or years!) before stumbling upon it again, and seeing how La Grande Guerre has trudged onwards in your absence.

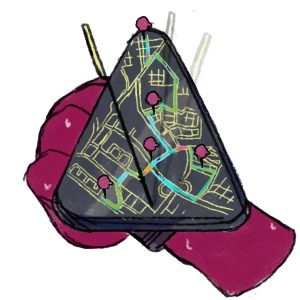

As for the drawings themselves, they transition between images, words, and maps.

The images are simply classic Craghead. They’re disjoined, as wars so often are. They sizzle and crackle.

As for the words, they aren’t mean to be read, exactly. Readers will sometimes be hard-pressed to make out every sentence in the poems and letters that punctuate La Grande Guerre. But, rendered in Craghead’s scrawny pencil line, they function as images as much as text – and indeed, as actual historical documents they’re more strictly representative of the war’s reality than imagined scenes of battle. They remind us that a treaty or proclamation can affect the reality on the ground just as much as shots exchanged or trenches dug.

The maps, then, are in the liminal space between words and images, between intangible text and tangible reality. They zoom out, reminding us that the war had geographic and not just temporal scale.

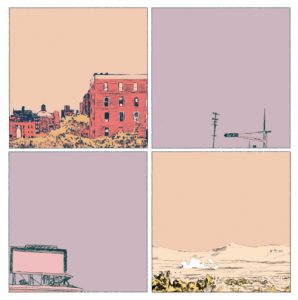

French illustrator and cartoonist Aseyn allows time to pass languidly in small sets of panels replete with pastel colors and empty space. It’s unclear, and perhaps purposefully so, whether these are complete works or snippets from a larger story, these isolated moments that push narrative almost entirely into the gutters. That’s not at all to say the images are thrown together haphazardly – there are clear echoes of story in the characters or images that reoccur, in the murmured words that appear very occasionally, in that pastel color palette from which Aseyn is able to extract so much range. Figures and landscapes both emerge from the edges of panels, which is certainly a compositional tool but also reminds us just how much might – or might not – be going on outside the purview of the images we can see.

Simon Moreton Transitions From Smoo to Minor Leagues

This interview was conducted in March 2016, when Moreton had announced the end of his series Smoo but not yet launched its replacement, Minor Leagues. Moreton has now released the first issue of Minor Leagues as well as several short works under an imprint he calls Lydstep Lettuce. The comics are sequentially numbered (LL1, LL2, etc.) and Moreton now prints all of his comics at home. A lo-fi approach that matches his lo-fi visual aesthetic as well as his wider artistic goals – some of which are discussed below.

QUESTION: You recently ended your series Smoo. How did you come to this decision? How do you think or hope ending Smoo will affect your work?

Simon: The decision came pretty easily. I’ve been making comics and zines for about 9 years now, and they’ve always been to one degree or another autobiographical. They became intimately involved in the rhythms of my life, how I made sense of the world and how I tried to communicate that with the world.

SMOO itself was born out of a specific period in my life, the last two thirds of my twenties, and on some level it still retained hidden rules established when I first started the comic, about what it was trying to be, what it had to contain, what I could or could not do.

When my personal circumstances began to change a couple of years ago, SMOO began to feel increasingly like it belonged to a previous period and that to properly explore my present and future, I needed to let it go. So I think the last three issues were a wrapping up exercise, catching up with my present and indicating towards a future. I felt that SMOO 8 was an important story that I’d been meaning to tell for some time, and I think 9 and 10 capture a transition and a new place.

As a vehicle it had bought me to where I was, but it wasn’t suitable for the new places I want to go, or terrains I want to explore.

What rules do you feel had emerged for you with Smoo? Have you set yourself any rules for the work you’re doing now?

That’s an interesting question because it’s something I’ve found very hard to articulate. I don’t think they were explicit rules, but I definitely felt beholden to a particular look and feel – size, paper stock – and stuck on one kind of narrative. For example, each issue ended up telling one story, even if it was made up of smaller stories. That made it hard to drop in a weird drawing, or a collage, or a gag strip, or even just a comic about something ‘off-topic’. So I’d have ideas for things and then go ‘oh that’s not right for SMOO’. But it didn’t feel right to be not pursuing ideas because I’d told myself that something had to be a certain way. When really, especially with self-publishing, you can do what you like.

I guess that’s my new rule: just be open and follow your nose.

You’re writing more prose lately. How is that going? What can prose do that images can’t?

I love writing. I always have done. I write a lot with my day job – I work as a researcher for a university by day, and I’ve got a PhD, so thinking and writing has become pretty core to what I do on a daily basis. I mean, it tends to be policy and academic and website copy stuff – but I enjoy the process, and I enjoy editing.

Of course that’s a very specific kind of writing and what I’d like to do is more exploratory. I’ve been reading WG Sebald again recently, Rings of Saturn, and the way he marries that visceral, dense, description, academic allusions and depictions of time and space. It’s amazing. It reminded me that writing can be whatever you want.

My choice to start writing, as much as any creative work is a choice, is about trying to bridge a gap, creatively and intellectually, between my day job and my art life. Like, I’m an academic, I work at a University, I’ve been trained in one way or another to think about the world in a particular way, and on the other hand I’m an artist and I make these minimal zines that struggle with big questions but in very quiet ways. What happens when those things meet?

In terms of what writing can do, there is a feeling that I get with reading good prose, and with good poetry, that I don’t get elsewhere. I can’t really explain it but, it’s just a really sense of the world opening up, a sort of marvel at how the rhythm and the flow of the words and the imagery and the juxtapositions do things to your brain. Drawings and comics do that too, but in a different way. So it’s learning to use those contrasting tools, I guess.

You’re going part-time at your job in order to have more time for art. How are you going to spend that extra time?

Between printing and assembling zines, answering emails and sending out orders and that sort of stuff, I am probably already doing a day a week on that alone, just in non-working hours. But the drawing and writing and thinking, knowing that I will have some time each week set aside just to do that, is amazing: to be given permission, and I mean permission from myself, to take this art thing seriously, to formally and visibly invest time into it and see where it takes me is incredibly exciting.

How do you think about time in relation to your work more generally? You’ve talked before about your style as in part a pragmatic choice given your limited time to draw. You generally produce pages pretty quickly.

Oh yes, the movement towards my current way of drawing was definitely a rejection of the Fordist model of comics production – script, pencil, ink, letter – that was far too time consuming. It killed things dead for me in lots of ways. It was boring.

At the same time, drawing the way I do now feels like a more honest way of making art. I think traditional comics work tries to obscure the fact that the thing on the page is in essence a reproduction of a drawing. The lines and colours and shapes, it all hides the human in the process. I’d rather see smudges and imperfections and things like that.

I like drawing quickly to capture an image, whether that’s something that’s in front of me, or something I’m trying to remember. It’s like a first-take mentality, about seeing what comes out when I put pencil to paper. That’s the moment things start to come to life. Sometimes I think about story a lot, before I start drawing, sometimes for months and months, and sometimes I don’t, but it doesn’t really take life until I draw it – like thinking hard about what you’ll say to someone, but then when you come to say it, it comes out differently. Because the drawing never comes out as you expect, because of what is lurking in the back of your brain, the non-verbal, almost subconscious stuff.

Don’t get me wrong: there is still process to my work. I use a lightbox to work up drawings into the right sequence, or for the right feeling; I reject sequences and worry about composition and pacing – I guess the technical and aesthetic elements of making comics. But I’m just more interested in minimising the violence that is done to a drawing on it’s journey to become an ‘image’, if that makes sense.

You said you reject sequences. Why is that? What does sequence mean to you?

When you work minimally, composition, rhythm and pacing become very important, almost like the sequencing of an album. I mean that both in terms of sequencing stories in a book or a zine, and sequencing images or panels within a story. The whole thing has to flow in a particular way – not always in a linear way or a smooth way, but in a way that serves the purpose of the image or story you are trying to invoke. As for when to reject or keep them, that’s a balance of intuition and hair pulling.

How do you navigate the balance (or tension?) between allowing your work to evolve naturally versus actively pushing towards directions you’d like to explore?

I was thinking about this just the other morning. I remember a couple of years ago visiting Orbital Comics in London to restock them with some zines. I was chatting with the great Camila who is their small press buyer about what I was working on, and she remarked how I had worked in so many different styles. At that point, I didn’t really think I had, but looking back now I see it’s true: what I thought was an evolution now appears to be more a series of rejections of earlier approaches. Well, not total rejections, perhaps, but iterations.

I don’t think there’s a tension for me. At the end of the day, I’m driven to make art by something very personal and I guess not being to hard on myself about how I explore that is the key thing. Giving myself permission to do whatever I like.

You mention rejections or iterations of earlier approaches. Do any important failures come to mind from your past work?

I don’t know about failures as such. I think I just get to a point with making things where I get frustrated, or bored, with how I am approaching a problem, the problem being how to tell a story. So I’ll be trying something, drawing a certain way, or writing a certain way and it just won’t be satisfying. Then I’ll change something and it’ll open new doors and I’ll pursue that. For that reason I think iterative is more the approach my art has taken: adopting elements that work at a point in time, letting go of those that don’t, and be willing to throw things out and add things in if I need to.

I mean, some of my early work is embarrassing, but is it a failure if got me here now? Simultaneously, I wouldn’t say anything I’ve done has ever been wholly successful, either. But then if I got something totally right, why would I carry on making stuff? The questions I want to ask in my work don’t have answers.

Autobio Comics: The Most Successful Mode of Comics Practice in the West?

Finally, Kim Jooha takes a step back to discuss a well-known trend in comics, and how the medium transitioned first towards and then away from it. Can a line be drawn, however tenuous, between the choices an individual cartoonists makes from one panel to the next and these wider trends in comics that are often visible only in hindsight?

Autobio comics is regarded as the dominant genre of North American alternative comics. Most comics that have received significant critical acclaim, not just inside the comics world but also in the mainstream, have been autobio comics. Notable examples include Maus (1986/1992), Safe Area Gorazde (2000), Fun Home (2006), March (2011) and Can We Talk About Something More Pleasant (2014). This is also true in the French language comics world, with works such as Fabrice Neaud’s Journal (1996-2002), Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), David B.’s Epileptic (2003), Dominique Goblet’s Pretending is Lying (2006), and Edmond Baudoin’s Couma Aco (1991) and Le Chemin de Saint-Jean (2002).

However, in both The Comics Journal’s ‘Top 100 Comics of the 20th Century’ (1999) and Rolling Stone’s ‘The 50 Best Non-Superhero Graphic Novels’ (2014), there are more fiction works than there are autobio works. Moreover, in the catalogues of notable alternative comics publishers of North America (Fantagraphics, Drawn and Quarterly, or Top Shelf) and France (L’Association, Fremok, Cornelius, Ego Comme X, Les Requins Marteux, or La Cinqueiem Couche), there are currently more fiction than nonfiction comics.

Autobio is indeed the genre that has grown most significantly since the alternative comics boom; but I would argue, it is not the most famous or the most dominant genre. Autobio is simply the genre that Western critics outside of the comics world seem to appreciate and engage in most easily. The aforementioned autobio comics led to the legitimization and consecration of comics in academia and literary circles in the Western world. However, this has not been the case in Japan, another huge comics market.

Why have autobio comics grown so much, in both production and quality, since the alternative comics boom in the 1980-90s in the West, but not in Japan? The answer should help explain the rise of autobio comics in both Franco-Belgian and North American alternative comics as well as the smaller impact of autobio comics in Japanese alternative comics.

The Authenticity Thesis Versus the Alternative Thesis

In Chapter 5 of his book Unpopular Culture, ‘Autobiography as Authenticity in Unpopular Culture’, Bart Beaty argues that autobio comics gave authenticity to both comics as literature/art and to the artists themselves. Autobio comics are generally the work of a single cartoonist, which differs from mainstream comics that hire writers and artists to work together following large corporations’ directions. I agree that this might be one of the reasons that autobio has been so appealing for artists in alternative comics, especially those works concerned in part with the autobio comics form itself, such as Maus, Faire semblant c’est mentir, and Journal.

This parallels the history of cinema. In the 50s, French critics of Cahier du cinema celebrated several Hollywood directors who had been considered only a part of a system, such as Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock; they developed the Auteur theory that the director is the artist who creates the work. By inventing the artist (auteur), they legitimized cinema as art. Before this, the director was merely considered as a manager who was in charge of film’s logistics. The auteur theory initiated European art cinema. Comics has had a similar tradition of finding artists from within a group of creators working within large corporations, such as Jack Kirby (Marvel) and Carl Barks (Disney). During the 90s, cartoonists proclaimed that they were independent and autonomous artists by telling their own authentic stories, rather than developing already written, unreal, and childish stories of fantasy worlds.

Beaty also argues that alternative comics worked as an alternative mode to colourful mainstream genre comics, contrasting superheroes in North America; SF and adventure in France; they were instead non-genre realism and black and white. Among the various non-genre approaches that developed (historical fiction, history, and biography, among others), autobio comics developed the most because it is both the easiest and the most authentic genre.

This also parallels the history of cinema. Italy’s post-war Neo-realism was the beginning of post-war European art cinema. Its proponents were against Hollywood’s fantasized reality and dramatization of narrative. Furthermore, The black and white form was considered more objective than the colour form in documentary film and photojournalism. In addition, the black and white form not only worked as an aesthetic choice but also as an economical choice for less financed alternative publishers. However, this also supports the authenticity thesis since such realist fiction and nonfiction works were deemed more “serious” and “legitimate” work and as an alternative to mainstream genre works.

Mainstream Manga is So Huge, It Offers No Place for Alternatives

Beaty’s alternative thesis can explain the absence of significant developments in autobio comics, and alternative comics more general, in Japan. The authenticity thesis offers no insight on this question. Manga is so heterogeneous and huge that it already contained alternatives. In manga, there are not only typical genre comics, such as fantasy, adventure, and SF, but also gritty realistic comics, such as Osamu Tesuka’s MW. The manga industry also had Shojo and Josei comics aimed at female audiences, which had been excluded in the Western comics market. The fact that manga is the only type of national mainstream comics that is popular in all three biggest comics markets (North America, French, Japan) shows how inclusive manga is.

This again parallels the cinema industry, as manga is like Hollywood cinema with its incredible popularity and diverse genres. During the 1950s-60s, when there were fewer audiences and European art cinema flourished, Hollywood transformed and absorbed European art cinema, which in turn developed as an alternative and became New Hollywood cinema. Today in Hollywood films, we can see abstract narratives or forms that were formerly only found in art cinema. Hollywood even began producing art cinema by purchasing independent production companies.

Alternative manga artists, most of whom worked for Garo magazine, deployed similar practices to their Western alternative counterparts. Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s Gekiga and Shinichi Abe’s I-Manga are both based on the artists’ personal experiences. While their works are acclaimed by comics critics, their influence has been quite limited compared to the Western alternative comics’ bestsellers such as Maus and Persepolis. Currently, there is only one alternative manga magazine in Japan, AX. In contrast, there are many small and micro publishers in the West that publish alternative comics.

Moreover, manga had been already in black and white. Color as an alternative to black and white would be attractive, but it would be expensive to produce, which makes it a prohibitive choice for financially less-established alternative productions. Therefore, alternative comics in Japan could not make distinctions large enough to separate itself from the mainstream.

Autobio Comics Today

In the West, autobio comics was the most successful of the various alternative modes of production that were explored. However, this does not mean that autobio had the highest quality. Autobio comics were more easily accepted as a legitimate cultural product in the pre-established book publishing industries and literary communities, including libraries and academia, compared to how art comics were received in the world of fine art.

In the introduction to Best American Comics 2007, Chris Ware says that comics needs autobiography since comics has not developed a language complex enough for the great storytelling. It could be that there is not as many great fiction comics compared to autobio comics because comics are not developed enough. In nonfiction comics, the contents dominate forms. Therefore, perhaps it was easier for autobio comics to be accepted as a legitimate cultural product than it was for fiction comics.

Moreover, autobiography is popular not only in alternative comics, but also in the general book publishing industry. Autobiography has an innate mass appeal. For example, in South Korea, where webcomics is one of the most popular forms of comics and even of media in general, autobio comics is the most popular genre. Autobio comics did not exist in the print comics era: publishers and editors did not believe it would sell. However, artists started producing autobio comics on their own and audiences started reading them fervently. In the similar way, with the rise of self-publishing, the inexpensive cost of black and white production, and the advent of a direct market, comics publishing and distribution became easier for the artist during the 80s and 90s. Artists started producing autobio comics, which mainstream publishers had not published. With ample supply, people started reading them a lot in the West.

These days, many nonfiction and autobio comics are produced in Japan too, such as Rokudenashiko’s What is Obscenity. However, whether works like this can be classified as an alternative mode of production as in the West, not just as a genre, is highly doubtful.